Chinese Premier Li Keqiang has stressed the importance of vocational education in boosting products made in China.

|

|

|

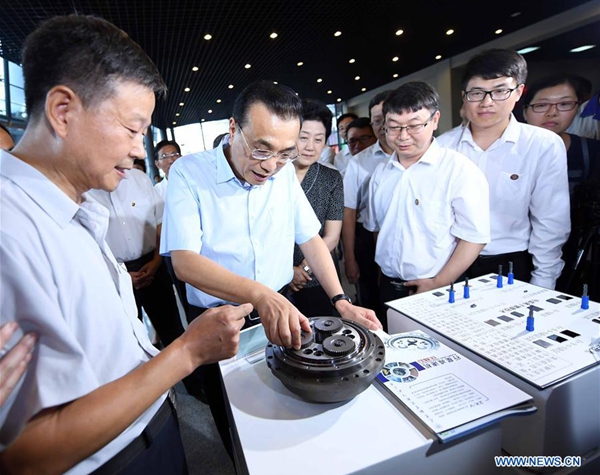

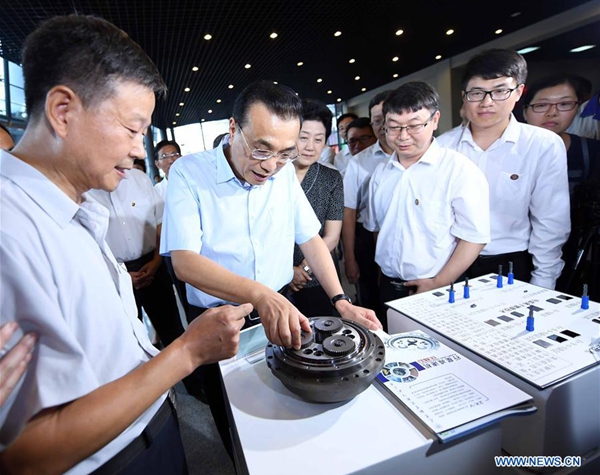

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang (2nd L, front) views technological achievements during an inspection to Tianjin University of Technology and Education in Tianjin, north China, Sept. 8, 2017. Li made an inspection here on Friday and stressed the importance of vocational education in boosting products made in China. During his inspection, the premier extended festive greetings to the teachers ahead of National Teachers’ Day, which falls on Sept. 10. (Xinhua/Zhang Duo)

|

Li made the remarks while inspecting Tianjin University of Technology and Education on Friday.

“While implementing the strategy of innovation-driven development, we need to encourage innovation on the one hand and translate good ideas into high-quality products on the other hand,” he said during the inspection ahead of Teachers’ Day, which falls on Sept. 10.

China needs to cultivate more professionals with higher quality, promote the spirit of the craftsman and encourage enterprises of various sizes to provide fine products amid efforts to boost the “Made in China” brand, Li said.

During his inspection, the premier extended festive greetings to the teachers.

He called for more efforts to foster a good environment of respecting teachers and valuing education and improve the quality of education to serve the country’s economic and social development.

read more