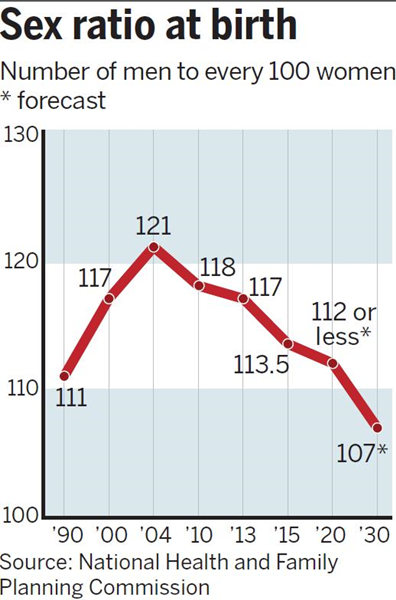

Report: China’s sex ratio to balance out by 2030

China’s sex ratio at birth will keep falling and eventually reach a balance within 15 years due to economic and social development and the relaxed family planning policy, the central government has predicted.

The ratio, which was 113.5 men to every 100 women in 2015, one of the highest in the world, is forecast to drop below 112 by 2020 and 107 by 2030, according to the National Population Development Outline released Wednesday by the State Council.

The normal range is between 103 and 107.

China’s sex ratio has been skewed by a traditional preference for boys. Population experts have estimated that the imbalance over the past 30 years has resulted in between 24 million and 34 million more men than women.

Wang Pei’an, vice-minister of the National Health and Family Planning Commission, has warned that the gender imbalance could result in serious social problems.

However, thanks to rising social awareness and government efforts, China’s sex ratio at birth has declined in recent years. A national guideline released this month said the authorities will continue to intensify the fight against fetus gender identification and sex-selective abortions.

Wednesday’s outline estimated that China will see its population peak at 1.45 billion around 2030.

To better monitor demographic changes, the country plans to establish a population forecast system based on censuses and samples surveys that will produce regular reports, the outline said.

It also said governments will continue to monitor the effect of the universal second-child policy as well as closely follow changes in the fertility rate to decide on possible adjustment to the family planning policy.

Yuan Xin, a professor of population studies at Nankai University in Tianjin, said the second-child policy will contribute to a lower sex ratio at birth because it will result in a higher fertility rate, but he added, “The family planning policy should be further relaxed so the ratio can be reduced to a balanced level.”

He agreed with predictions that the second-child policy will result in a peak in births in the next few years, but he warned the effect may decline gradually due to the reduced number of women of childbearing age.

About 90 million women became eligible to have another child when the second-child policy was introduced early last year. However, half were aged 40 or older, meaning they are less likely to give birth again, Yuan said.

“Adjustment to the policies should be based on consistent monitoring of the population. A scientific evaluation should be made,” the professor added.