1. How can banks address capital shortfalls in line with EU state-aid rules?

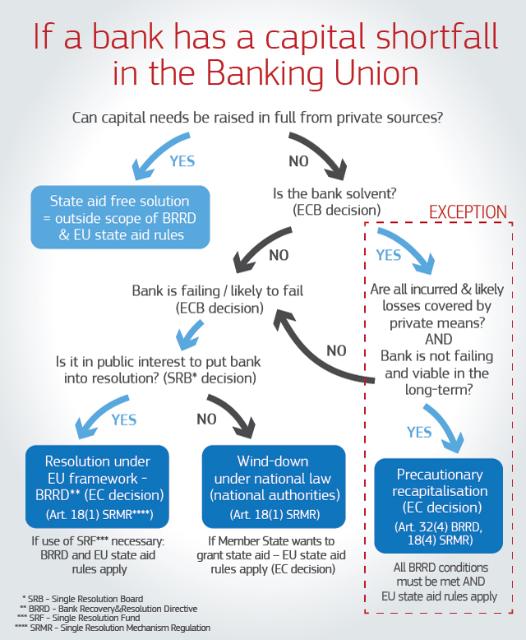

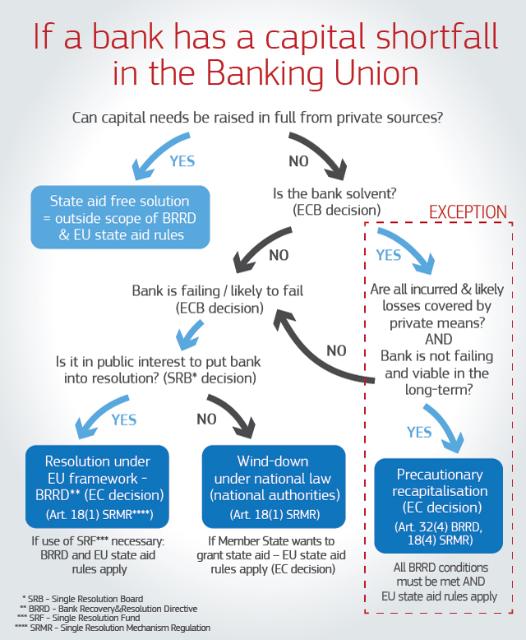

If a bank needs capital, it does not necessarily mean that it is failing or about to fail. There may be a number of options for banks to address their capital shortfall without triggering resolution and in line with EU state aid rules. Whether an option is available in a specific case depends in particular on the bank’s financial position, the market interest, decisions by the Member State concerned as well as by responsible supervisory and resolution authorities

a) A bank can raise capital on the market or from other private sources. This falls outside the scope of the EU bank resolution framework and state aid control.

For example, in February 2017, shareholders of the Italian bank UniCredit approved a recapitalisation of €13 billion from private sources.

b) A Member State can decide to intervene in line with market conditions. This also falls outside the scope of the EU bank resolution framework and state aid control. A state intervention is in line with market conditions if a private economic investor would carry it out on the same terms.

For example, thePortuguese recapitalisation of the fully state-owned bank Caixa Geral de Depósitos in March 2017 was carried out on market terms and therefore did not involve state aid in favour of the bank.

c) The EU bank resolution framework[1] also foresees the exceptional possibility of a precautionary recapitalisation, which allows the use of public funding subject to strict conditions and in compliance with state-aid rules. For example, in 2015 the Commission approved Greece’s precautionary recapitalisation of two Greek banks, Piraeus Bank and National Bank of Greece, under EU rules. The Commission has also reached an agreement in principle with Italian authorities to enable a precautionary recapitalisation of Italian Monte dei Paschi di Siena in June 2017.

(See more details under Question 2.)

However, the responsible supervisor, i.e. the European Central Bank (ECB) in the Banking Union, will declare a bank failing or likely to fail when it infringes or is likely to either i) infringe the requirements for continuing authorisation, ii) when the assets of the bank are or are likely in the near future to be less than its liabilities, iii) when the bank is or is likely in the near future to be unable to pay its debts as they fall due, or iv) when the bank needs public support unless special conditions are met such as for precautionary recapitalisation (Article 32(4) of the BRRD).

If the ECB declares a bank failing or likely to fail, the responsible resolution authority, i.e. the Single Resolution Board (SRB) in the Banking Union has to decide whether it is in the public interest to put the bank into resolution via the Single Resolution Mechanism (for example, the resolution of the Spanish Banco Popular in June 2017), or whether a bank could be wound down under national insolvency law (for example, the liquidation of Italian Banco Popolare di Vicenza and Banca Veneta in June 2017 and Italian Banca Romagna in July 2015). Here, resolution should be the exception to the rule of national insolvency and the question of whether there is a public interest in applying that exception will be determined by the SRB with respect to the question whether certain resolution objectives set out in Banking Union rules can be fulfilled better in resolution than in national insolvency.

(See more details under Question 3.)

2. What are the conditions of a precautionary recapitalisation?

For banks that are solvent and not failing or likely to fail, the BRRD contains the possibility of providing State aid. This is called precautionary recapitalisation. It is subject to strict conditions under the EU banking framework, respectively, to ensure that the aid is indeed provided on a precautionary basis, and conditional on final approval under EU State rules.

The EU banking framework requires that State aid in this context can only be granted as a precaution (to prepare for possible capital needs of a bank that would materialise if economic conditions were to worsen significantly) and is therefore reserved for banks that are solvent and not failing or likely to fail. The option of precautionary recapitalisations for solvent banks under the EU banking framework was agreed between co-legislators in the European Parliament and the Council to have strict conditions.

The main conditions for a precautionary recapitalisation are:

-

the ECB needs to declare that the bank is solvent;

-

the State support shall not be used to offset losses that the institution has incurred or is likely to incur in the future,

-

the State support is temporary (i.e. the State should be able to recover the aid in the short to medium term), and

-

the State support has received final approval under EU State aid rules.

In particular, the State aid crisis rules on banking (2013 Banking Communication) require that:

-

the use of taxpayer money is limited through appropriate burden-sharing measures (shareholders and subordinated debt holders contribute). Depositors and senior creditors are not required to contribute under State aid rules,

-

a credible and effective restructuring plan to ensure the bank is viable in the long-term without further need for State support,

-

distortions of competition are limited through proportionate remedies.

3. What happens if a bank is failing / likely to fail?

If the responsible supervisor declares a bank failing or likely to fail, it is for the responsible resolution authority to decide whether it is in the public interestto put a bank into resolution.

Resolution under the Single Resolution Mechanism

In the Banking Union, if the SRB considers that it is in the public interest, based on the resolution objectives, the bank is put into resolution in line with the Single Resolution Mechanism Regulation (SRMR).

Resolution measures taken by the SRB require a resolution decision by the Commission under the SRMR.

The SRMR requires that the bank’s losses will have to be covered by the bail-in of shareholders and creditors (at least 8% of the bank’s liabilities) before the Single Resolution Fund can be accessed. This may also require bailing-in senior debt and, where necessary, uncovered deposits.

If the Single Resolution Fund is used, the Commission will also have to make an assessment to authorise its use under EU State aid rules (just as it would for interventions of National Resolution Funds of Member States that do not participate in the Banking Union).

National insolvency law

If the SRB considers that resolution action is not warranted in the public interest, EU law stipulates that the bank is wound down in line with national insolvency law. It is the responsibility of the national authorities to apply national insolvency law.

If the Member State considers it necessary to grant State aid in the context of such national insolvency proceedings, it has to notify such measures to the Commission under EU State aid rules. Burden-sharing requirements apply, i.e. shareholders and holders of subordinated instruments have to contribute in full to the cost of the measures. Depositors and senior creditors are not required to contribute.

4. Why do EU rules allow state aid to banks in liquidation?

While the winding up of smaller banks may not affect the European financial system, their market exit may still have effects in the regions where such banks are most active. Therefore, outside the European banking resolution framework, it is for Member States to decide whether they consider a bank exit to have a serious impact on the regional economy, e.g. on the financing of small and medium enterprises in the regional economy, and whether they wish to use national funds to mitigate these effects. EU state aid rules, in particular the 2013 Banking Communication, foresee this possibility, subject, amongst other things, to burden-sharing rules and clear commitments that the entities effectively exit the market to ensure that competition distortions are minimised.

5. What are the conditions that need to be met for state aid to banks in liquidation to be approved?

It is the responsibility of the national authorities to apply national insolvency law and to decide, where a possibility for a sale of the bank’s activities is foreseen in the law, whether to make use of it. Should the national authorities envisage to grant public support to such an operation under insolvency law, EU State aid rules require that the cost be reduced by a sales process that is competitive, open and fair, to make sure that the activities are sold to the best bid available so that there is no aid to the buyer. They also require burden-sharing of shareholders and junior creditors.

Winding up a failing bank protects the healthy competitors in the market; therefore if a Member State would deem State aid necessary to facilitate the liquidation of a bank by a sale of assets and liabilities, these activities should be restructured and downsized by the buyer to ensure that distortions to competition from the aid are limited.

6. What is the role of the Commission and other institutions?

The European Commission does not supervise banks or take decisions on how to recapitalise banks. In the Banking Union, this is the role of responsible national authorities and/or the ECB and the SRB. The Commission applies EU rules in a consistent and equal manner, irrespective of the Member States and the banks involved. In applying EU rules, the Commission’s objective is to ensure fair competition between banks in the EU’s Single Market.

In the Banking Union:

-

Whether a bank is in need of regulatory capital, is the assessment of the ECB. Such an assessment may be made on the basis of an asset quality review and/or a stress test.

-

Whether a bank is failing or likely to fail is the decision of the ECB and the SRB.

-

If a bank is declared failing or likely to fail, it is the decision of the SRB whether resolution action is warranted in the public interest, or whether a failing bank can be put into insolvency proceedings.

-

In case the SRB considers it to be in the public interest, it will then put the bank in resolution and determine the resolution strategy and the tools according to the resolution objectives. It is also for the SRB to decide whether the use of the Single Resolution Fund (SRF) is necessary.

-

The Commission has to endorse the SRB’s resolution scheme under EU banking resolution framework, and in case the SRF is accessed, the Commission needs to authorise it under EU State aid rules.

-

In case a failing bank is put into insolvency under national rules, this proceeds according to the national legal order.

-

Whenever aid is notified by the competent authorities in any of these circumstances, the Commission’s mandate is to verify that the planned state intervention comply with EU rules, in particular the SRMR / BRRD and EU state aid rules.

Outside the Banking Union the same rules apply but are enforced by national counterparts.

7. What about retail investors who were mis-sold?

Retail investors should be adequately informed about potential risks when they decide to invest in a financial instrument (as required under the EU Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID 1) and implemented into national law). If a bank fails to do so, in principle, the responsibility of addressing the consequences of mis-selling lies with the bank itself. Such compensation is an entirely separate consideration to burden-sharing under EU State aid rules.

There are different ways to allow retail investors who have been mis-sold to be compensated. This is a decision for the responsible national authorities and/or the bank to take.

In situations where banks that have mis-sold financial instruments have left the market, it is up to Member States to decide whether to take exceptional measures to address social consequences of mis-selling as a matter of social policy. This falls outside the remit of State Aid rules.

For example, Italy set up a scheme to compensate retail investors who were victims of mis-selling of junior bonds by four Italian banks that were resolved in November 2015 (Banca delle Marche, Banca Popolare dell’Etruria e del Lazio, Cassa di Risparmio di Ferrara and Cassa di Risparmio della Provincia di Chieti).

8. How did EU rules for state aid to banks evolve?

The applicable EU rules were updated a number of times, in consultation with all EU Member States and the European Parliament, to adapt to the evolution of the financial crisis and reflect the lessons learnt. The rules in force on State aid to banks are based on an exceptional rule of the Treaty, 107(3)(b). As set out in point 93 of the 2013 Banking Communication, the Commission will review the Communication as deemed appropriate, in particular so as to cater for changes in market conditions or in the regulatory environment which may affect the rules it sets out.

Depending on when Member States choose to address problems of their banks and to come forward with solutions to restore their viability, different rules might apply:

The period between 13 October 2008 and 31 July 2013 – Throughout 2008 and 2009, the Commission adopted a comprehensive framework for state aid to the financial sector during the crisis. This included the 2008 Banking Communication and different Communications with specific guidance on recapitalisations, impaired assets and bank restructuring. They were prolonged in 2010 and 2011. Given the great uncertainty about the banks’ problems in the early stages of the financial crisis and the need for quick action, the Commission allowed “rescue aid“. This means that state aid could be approved on a temporary basis. Member States had to submit a restructuring plan for banks receiving rescue aid within six months for final approval by the Commission.

From 1 August 2013 – The Commission adopted a new Banking Communication (see Memo, full text here), which is in force today. It replaces the 2008 Banking Communication and supplements the specific guidance on recapitalisations, impaired assets and bank restructuring. In consultation with the Member States, these rules introduced a more effective restructuring process for aided banks and strengthened burden-sharing requirements, asking shareholders and subordinated debtholders to contribute before aid could be granted. As Member States should be able to anticipate the problems of banks better, state aid can no longer be approved on a temporary basis but only on the basis of an agreed restructuring plan and after all private capital-raising measures have been exhausted.

From 1 January 2015 – The Bank Resolution and Recovery Directive entered into force as part of the EU’s Banking Union. This Directive introduced the default option for failing banks to go into normal insolvency proceedings. Only if the resolution authority decides that it is in the public interest to do so, can a bank be resolved in line with the Bank Resolution and Recovery Directive. The Bank Resolution and Recovery Directive also required that state aid to failing banks notified to the Commission after 1 January 2015 can only be granted if the bank is put into resolution. The only exception is a so-called “precautionary recapitalisation”, allowing state aid outside of resolution in narrowly defined circumstances. EU State aid rules continue to apply in full in parallel.

From 1 January 2016 – The bail-in requirements for banks in resolution under the Bank Resolution and Recovery Directive entered into force in all Member States that had not already implemented them in 2015. This means that in resolution contributions from the Single Resolution Fund can only be made after a bail-in of at least 8% of the bank’s total liabilities. This may also require converting senior debt and uncovered deposits. Any contribution of the Fund is subject to a State Aid Decision by the Commission. EU State aid rules continue to apply in full in parallel.

Under the new rules, the resolution process is managed by a resolution authority – national or the Single Resolution Board for the euro area countries.

[1] Within the Banking Union, “EU banking framework” refers to the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) and the Single Resolution Mechanism Regulation (SRMR).