Donor shortage threatens rare-blood carriers

|

|

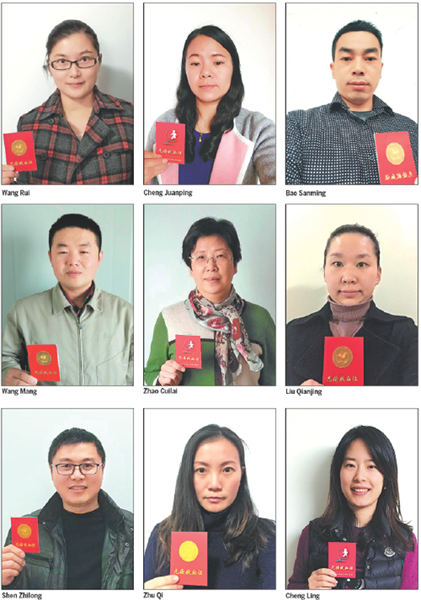

Volunteers proudly display their blood donation certificates. The China RH Union is looking for more donors to help the small number of people with rhesus negative blood in China. [Photos/China Daily] |

Only a small number of people in China have rhesus negative blood, and a lack of supplies can be potentially life-threatening if they need an urgent transfusion. Zhou Wenting reports from Shanghai.

Xie Yingfeng recently quit his job to devote himself to an NGO that helps people with a rare blood type find donors who could potentially save their lives.

There are four human blood types: A, B, AB, and O. Each has a rhesus factor, either positive or negative. Generally, people with rhesus negative blood can only receive transfusions of their own type, while rhesus positive carriers can receive blood from both positive and negative donors.

Only three in every 1,000 Chinese has rhesus negative blood, so in the words of an old phrase they are “as rare as a panda”, which has led to it being known as “panda blood”. Moreover, many people have no idea whether their blood type is rhesus negative or positive until they need a transfusion.

The small number of people with rhesus negative blood means there is an equally small number of donors, which poses serious problems for people who require urgent transfusions, especially women who have postpartum hemorrhages.

Volunteers

Xie, 38, is the Shanghai regional head of the China RH Union, an NGO founded by volunteers in Beijing, most of whom have rhesus negative blood. Nationally the organization has about 4,000 members.

Every year, the Shanghai branch assists about 40 people who approach it in search of blood donations. For each case, Xie may receive as many as 200 phone calls from the patient’s family, volunteers, friends and even strangers who have read online posts for donors.

“It’s hard for me to do 9-to-5 office work because my phone is likely to ring constantly,” said the former construction materials salesman, who is currently living on his savings, but is considering selling delicacies from his hometown of Urumqi, capital of the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, to earn more money.

On a typical day, he spends hours confirming patients’ requests, rushing to the hospital or calling their physicians, and accompanying volunteers when they donate blood.

“The aim behind the union is that when people of the same kind are in trouble, we can stand up for each other,” said Xie, who is rhesus negative himself. In the 12 years since it was founded, the union has helped more than 3,000 people nationwide.

Having spent 12 years helping other people, Xie has become less interested in material wealth, which is another reason he quit his job.

The union was founded in 2005 by Beijing resident Wang Yong, who was deeply touched by media coverage of a rhesus negative leukemia patient who had been forced to abandon medical treatment because of a shortage of suitable donors.

Although Wang has a positive blood type, he began researching the condition and discovered that millions of people across the country are carriers: “I was an IT engineer, so I set up an online platform to make it less difficult to obtain blood for this small group.”

At first, the union-which has branches in 26 provinces and municipalities-received just one or two calls a week, but it now fields as many as 20 a day. The regional heads, who never turn off their cellphones in case they are called for help, collect information about patients, verify their medical information, post messages to volunteers via an online chat group and search for donors.

A precious resource

According to the union’s rules, six months must elapse between each donation, while people recovering from a cold or who have taken medicine have to wait a week after the all-clear before they are allowed to give blood. Women who are menstruating or breastfeeding are not allowed to donate. “Most of us don’t visit centers to donate blood regularly. Our resource is fairly precious, so we must make every drop count,” Xie said.

According to Wang, the largest amount donated by a single volunteer was 20,000 cubic centimeters, roughly five times the volume of blood in the average adult body, which required at least 50 separate donations.

“Some volunteers have stopped smoking or drinking alcohol and going to bed late to ensure they are healthy enough to make an urgent blood donation. Some slender women have even attempted to gain weight to meet the requirement that donors must weigh at least 45 kilograms,” he said.

The regional heads usually look for candidates within their home province or municipality, but sometimes volunteers rush to distant locations to donate blood.

In February, the union’s branch in Anhui province was looking for donors with B negative blood for a 60-something woman who was awaiting surgery. No one could be found within the immediate locality, but Kang Huiming, a primary school teacher in Lianshui county, Jiangsu province, volunteered to help. That night she asked a friend to drive her to the hospital, six hours from her home.

“It’s not about showing your benevolence-it’s about saving a life,” Kang said.

Although the number of members has grown gradually, some quit the union after a couple of years.

“When they first join, some people feel like they are superman and can help anybody. But if their help fails to save a life, it’s hard to drag them out of the low mood,” Wang said.

Xie, in Shanghai, recalled an unsuccessful attempt to save the life of a 7-year-old girl with leukemia. Having received a phone call from the girl’s mother, he immediately started looking for donors. Eventually, he contacted a suitable volunteer, but the man was on a business trip to Henan province in Central China. Desperate to help, the volunteer concluded his trip, flew back to Shanghai and rushed to the hospital. Unfortunately, the girl died just as he arrived.

“Many of the volunteers were sleepless that night. The volunteer who flew back even blamed himself for taking the trip,” Xie said.

Others have been lured away by money. Trading in blood is illegal under Chinese law, but “black” collection and supply agencies still exist. According to Xie, 400 cc of rhesus negative blood can fetch more than 20,000 yuan ($2,900) on the black market.

Decisions and pressure

The biggest pressure Xie faces comes when he has to decide whether to ask volunteers to donate blood to someone with a minimal chance of survival.

In May, he was approached by the father of a 2-year-old boy who had double kidney failure and was about to have a transplant. The man was hoping to obtain 3,000 cc of rhesus negative blood.

“The hospital said the transplant stood very little chance of success. To provide 3,000 cc, we would have needed eight donors, but their blood might save eight other patients who have a better chance of survival,” he said. Reluctantly, Xie declined the father’s request. He later discovered that the parents had bought blood from illegal dealers, but the boy died during surgery.

“In such cases, I shoulder overwhelming pressure from the volunteers, the patient’s family and my friends, but after all these years, I’ve become more rational. The truth is that we can’t always provide assistance in time or help people endlessly,” he said.

Wang has considered leaving the union on several occasions, but hasn’t been able to bring himself to abandon the cause.

“The simple act of disseminating a message can sometimes save the life of someone who may have no other way out,” he said.