International comparisons of Education funding

I have received the enclosed letter from the Secretary of State for Education:

With the new academic year now underway throughout the country, I wanted to let you know about some new international comparisons of education funding, and to update you on some other education matters, which may be of interest to schools in your constituency.

International comparisons

This week saw the publication of the 2018 edition of the OECD’s ‘Education at a Glance’, the definitive comparative guide to education systems in the developed world. It shows:

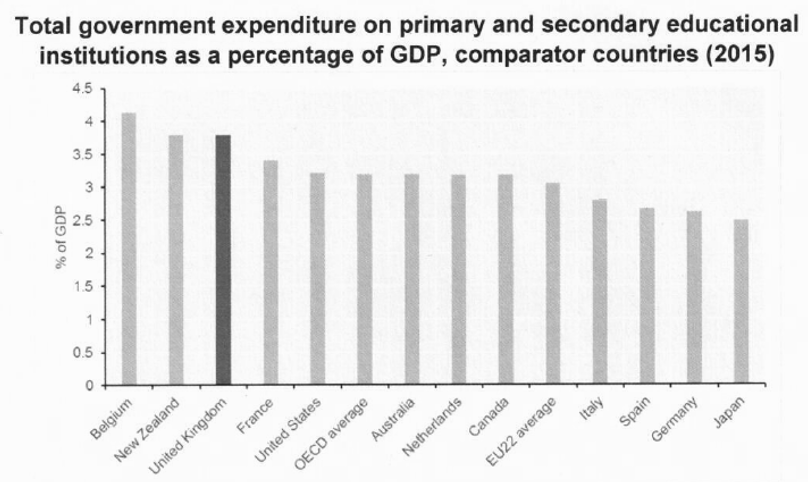

• The UK spends more on state-funded primary and secondary education, per pupil, than France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Australia and Canada.

• The UK spends more on state-funded primary and secondary education as a proportion of GDP than all those countries above, plus the US.

• Pre-school education at ages 3 and 4 is now near universal in the UK.

• The UK’s universities remain the world’s second most popular choice for international students, after only the US.

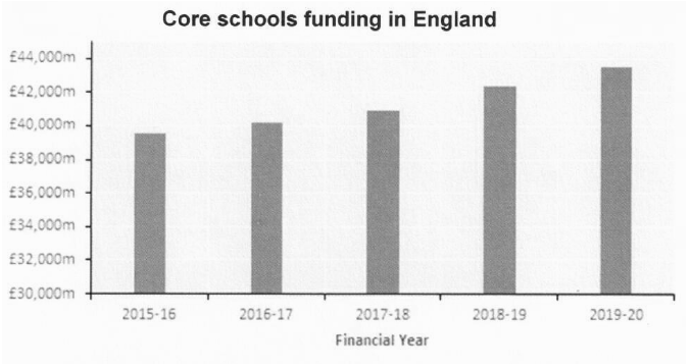

There is more money going into our schools than ever before; as the graph below shows, budgets have risen every year since 2015. This year the core school budget increased to £42.4 billion and will rise further to £43.5 billion in 2019-20. This increase follows the additional £1.3 billion, over and above what was promised at the last Spending Review, added to school budgets by prioritising front-line spending within the Department for Education’s budget.

Funding for the average primary school class of 27 pupils this year is £132,000, £8,000 more in real terms than in 2008. The same 27 children will be funded on average £171,000 when they move in secondary school, a real terms rise of £10,000 compared to a decade ago. Figures from the independent Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) show that real terms per-pupil funding in 2020 will be more than 50% higher than it was in 2000. Overall, the latest published figures for England’s schools show a cumulative surplus of more than £4 billion, against a cumulative deficit of less than £300m. The proportion of schools in deficit, or in a trust with a deficit, was lower in 2017 than in 2010.

In addition, we are investing £6 billion in the High Needs budget, which covers support to children with complex special education needs and alternative provision across England. This is now at a record high, 20% more than in 2013-14.

The national funding formula

Alongside this extra funding, we have also taken on the historic challenge of introducing a fair national funding formula, to ensure school funding is distributed to where it is needed most. Since April this year, funding has been directed based on schools’ and pupils’ needs and characteristics – not accidents of geography or history.

Schools are already benefitting from the gains delivered by the national funding formula. Next year, schools that have been historically underfunded will attract up to 6% more, per pupil, compared to 2017-18 – a further 3%, per pupil, on top of the 3% they gained in 2018-19 – as we continue to address historic injustices.

The very minimum additional amount that any school attracts in 2018-19 as a result of the national funding formula is 0.5% per pupil, compared to 2017-18 baselines – though the final amount received by schools can be affected by decisions made at a local level, for example if the local authority decides to transfer some funding to its High Needs provision.

Teachers’ pay and pensions

There can be no great schools without great teachers. That is why we have committed to making sure that teaching remains an attractive and fulfilling profession. Our classroom teachers in their twenties earn around £2,000 per year more than the average graduate in their twenties and the average salary for all teachers is £38,7000 (£35,400 for classroom teachers, £58,100 for those in leadership positions).

Just before summer break, we announced the biggest increase to teachers’ pay since 2010. This includes a 3.5% increase to the main pay range, building on last year’s 2% uplift, which will raise starting salaries significantly and increase the competitiveness of early career pay. We have also announced uplifts of 2% to the upper pay range (for more experienced teachers) and 1.5% for school leaders.

These increases will be fully funded, with a teachers’ pay grant totalling £508 million over 2 years, over and above the funding that schools receive through the national funding formula. This will cover, the difference between this award and the cost of a 1% award that schools would have been planning for. We are announcing further details of this grant today, with allocations made to schools later in the autumn term.

HM Treasury has also recently published changes to the Teachers’ Pension Scheme (along with other public sector pensions). We intend to fully fund schools for the additional pressure that the increase in pensions contributions will place on their budgets. The core schools budget will continue to be protected in real terms per pupil. The precise impact of the pensions changes is now being calculated, and we will consult on the distribution of this funding, and announce it in good time before schools have to start paying the new contributions in September 2019. The Teachers’ Pension Scheme remains one of the best pension plans in the country.

Misleading claims from 3rd parties

You may have seen figures based on the flawed calculations of the “School Cuts” campaign. This campaign misrepresents the funding schools will receive, presenting historical pressures on school budgets as if they were still to occur.

We have continued to challenge the misleading claims made on their website and in the media. As a result, the campaign has rowed back on some of these and made changes to their website. For example, the campaign claimed that per-pupil funding has reduced in real terms in 2018-19, but had to admit that they simply got their numbers wrong. They have since accepted what the IFS has confirmed – that the schools budget will be maintained in real terms per pupil over 2018-19 and 2019-20.

Support to schools

Of course, even with this protection of the overall schools budget, cost pressures in recent years have meant, in individual cases, budgets can feel tight.

We have just launched a Supporting School Resource Management document which provides schools with practical advice on savings that can be made on the £10 billion non-staffing spend spent across England last year. This summarises the support the department is making available to help schools reduce cost pressures and make every pound count to produce the best outcomes for pupils.

One of the tools available is our financial benchmarking service. This helps schools to compare their spending on a wide range of costs with that of similar schools, to share good practice and to identify where they can make savings so that they can direct the maximum resource into good quality teaching. Using this service, schools in your constituency can compare themselves on individual cost categories, to see where savings may be possible, to re-invest in frontline education.

Among the new initiatives, we are bringing forward our Supply Agency Framework and purchasing programmes across spend areas as diverse as facilities management, stationary, energy and software licences. Thousands of schools are already saving significant sums on insurance through our Risk Protection Arrangement programme. The new, free Teacher Vacancy Service will help bear down on recruitment costs. It is currently being piloted in Cambridgeshire and the North East.

We are providing direct support to schools and trusts with particular financial challenges and are increasing the number of School Resource Management Advisers to be deployed in 2018/19. We are also encouraging schools to integrate their curriculum and financial planning to inform decision-making on the deployment of teaching staff.

Quality expansions

Between 2004 and 2010, there was a net loss of 100,000 school places. By contrast, since 2010 we have brought about an ambitious expansion in our school estate to ensure we cope with population growth, and that parents have high-quality choices (this year 97.7% of families got one of their top 3 choices for primary and 93.8% did for secondary).

We have opened 53 new free schools this month, along with one University Technical College. We are enabling selective schools to expand if they come forward with a compelling plan for how they will widen access. And we have created a route for new Voluntary Aided schools to open. All told, we will have created a million more school places this decade – the biggest expansion of school capacity for at least two generations.

Rising standards and narrowing the gap

All this work is paying off. There are now 1.9 million more children being taught in good or outstanding schools. This means 86% of children attend good or outstanding schools – up from 66% in 2010. Our primary children have risen from 19th in 2006 to joint 8th in 2016 in the world reading comparisons. And young people are now being better prepared for work and further study through reformed GCSE and A Level courses.

The attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and their better off peers has also fallen at every stage of education: 11% for early years (since 2013), 10% at both key stage 2 and GCSE (since 2011), and we are seeing record numbers of university admissions for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds. This is in addition to a record low in the number of 19 year olds not reaching the equivalent of Level 4 or above in England and Maths.

Yours ever

Damian Hinds

Secretary of State for Education