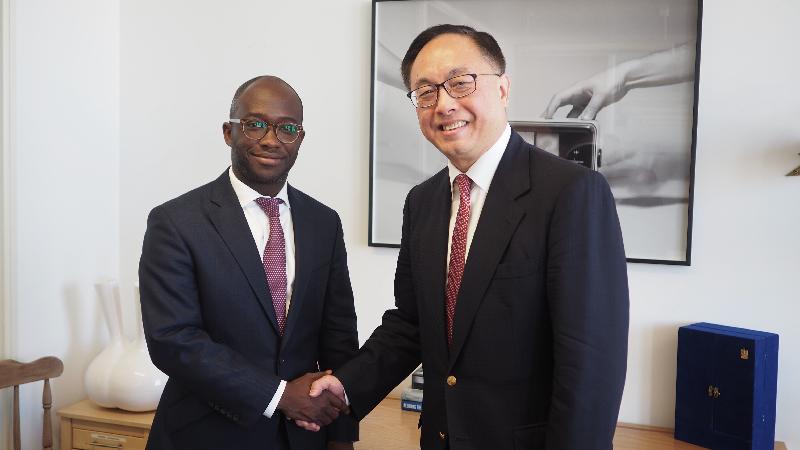

Following is the speech by the Secretary for Innovation and Technology, Mr Nicholas W Yang, at a luncheon with key players in the innovation and technology (I&T) sector in London co-organised by the Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office, London and the Invest Hong Kong (InvestHK) today (June 26, London time):

Lord Wei (The Lord Wei of Shoreditch, Mr Nathanael Wei), distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen,

It gives me great pleasure to join the luncheon today organised by the Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office and the InvestHK. This is also my first official visit to the United Kingdom as Secretary for Innovation and Technology of the Hong Kong SAR Government.

Today, I would like to share with you the latest initiatives of the HKSAR Government to drive innovation and technology development, leveraging on Hong Kong’s unique competitive advantages under the “one country, two systems” arrangement.

There are ample opportunities for further collaboration between Hong Kong and the UK, which have long enjoyed excellent relations. During the Great Festival of Innovation held in Hong Kong in March 2018, we issued a Joint Statement on Closer Collaboration between the UK and Hong Kong on Trade and Economic Matters. This statement highlighted innovation and R&D as priority areas for further collaboration. We also agreed on the key areas to focus on, including smart cities, healthcare technologies, artificial intelligence and robotics, and FinTech.

Hong Kong is economically and culturally China’s most internationalised city, and has always been the premier gateway to the Mainland of China. Hong Kong has unique competitive edges, such as the close proximity to the fast-growing market of the Mainland of China, a competitive tax regime, the rule of law, an open and free market and a can-do mindset in the business sector.

Last month, the International Institute for Management Development’s (IMD) latest World Competitiveness Yearbook ranked Hong Kong the second most competitive economy globally, out of the 63 economies assessed, just behind the US. We are consistently ranked the world’s freest economy and the third most competitive global financial centre. You can read more about these figures in the booklet we are distributing today.

With these traditional strengths, we are determined to develop Hong Kong into a knowledge-based economy and an innovation hub. Our aim is develop new economic sectors to boost Hong Kong’s competitiveness, improve our citizens’ quality of life and address social challenges through applied innovation and technology. In slightly more than two and a half years, we have committed at least HK$78 billion (GBP 7.5 billion) to promote I&T development, including an unprecedented HK$50 billion allocated in this year’s Budget. I&T development in Hong Kong today is exciting and energetic.

Investment into Hong Kong’s innovation and technology infrastructure by the private sector has also been growing significantly in the past few years. Three new submarine cables, providing direct links between Hong Kong and the US, are in the pipeline and, when completed in about three years’ time, they will triple the capacity of our existing submarine cable systems. Investors, including Facebook, Google, Telstra, and NEC, chose Hong Kong as a landing point for their huge investments, strengthening our potential to become the region’s data hub. Google Cloud Platform region, Amazon Web Services and Huawei Cloud are all setting up their service region in Hong Kong.

Venture fund investments in Hong Kong are burgeoning too: Alibaba Entrepreneurs Fund offers HK$1 billion to entrepreneurs and young people to grow their businesses; Sequoia Capital set up a Hong Kong X-Tech Startup Platform to provide angel and early stage investment to start-ups. Leading global R&D institutions are also setting up in Hong Kong. These include Karolinska Institutet of Sweden, which opened its first overseas research facility in the Hong Kong Science Park, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), which established an Innovation Node in Hong Kong to promote innovation practice and entrepreneurship for MIT and Hong Kong students. Last week, the renowned Pasteur Institute of France also joined the band wagon.

Hong Kong’s technology start-up scene is also blossoming. The number of start-up companies in Hong Kong increased by 16 per cent (from 1 926 in 2016 to 2 229 in 2017). Private capital investment in start-ups is also increasing. With the launch of the Innovation and Technology Venture Fund this year, under which the Government co-invests with venture capital funds on an investment ratio of about 1:2, we hope to provide an incentive for venture capital investors to inject more smart money into our local start-ups.

Meanwhile, the 13th National Five-Year Plan has pledged support to develop innovation and technology in Hong Kong. Leveraging our competitive strengths across a broad spectrum of areas, we participate in the Mainland’s technology initiatives.

President Xi Jinping’s recent instruction to the State Council of China affirms that Hong Kong has a solid science and technological foundation and a large pool of technology talent and promises the Central Government’s support to Hong Kong to become an international innovation and technology hub.

Following the instruction, the Ministry of Science and Technology of China announced new policies to enable Hong Kong universities and research institutions to tap into research resources in the Mainland and participate in the nation’s major technology missions. This is a major policy breakthrough, as it allows Hong Kong researchers to access the science and technology funding from national programmes of the Central Government and use such funding in Hong Kong. We believe that the new policy will inject further impetus into our research sector, and help leverage Hong Kong’s advantages to develop the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Bay Area into an international I&T hub.

The Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Bay Area has a strong focus on I&T. The 11 cities in the Bay Area, including nine cities in Guangdong plus Hong Kong and Macao SARs, offer not just a huge market for technology enterprises, but a highly efficient manufacturing base for turning research outcomes into prototypes and products. Last July, the Governments of the three places signed a Framework Agreement to develop the Bay Area, and I&T is a key co-operation area. We have since been working closely with relevant parties, and look forward to the announcement of the Bay Area Development Plan shortly. With Hong Kong’s sophisticated infrastructure and strong research capabilities, we are confident that the SAR will play an important and unique role in building an international I&T hub in the Bay Area. The development of the Bay Area is poised to present huge opportunities for individuals and enterprises alike.

A key infrastructure development related to the Bay Area is the new Hong Kong-Shenzhen Innovation and Technology Park (the Park) in Lok Ma Chau Loop at the boundary of Hong Kong and Shenzhen. This Park, spanning about four times the size of the existing Hong Kong Science Park, will become Hong Kong’s largest-ever I&T platform for Hong Kong, Mainland and international co-operation in scientific research, higher education, and creative and culture industries, where top-notch talents can collaborate.

Hong Kong is well-positioned to attract renowned researchers and foreign companies to conduct R&D. We will form two research clusters in healthcare technologies and artificial intelligence and robotics, with HK$10 billion dedicated funding from the HKSAR Government. Our aim is to attract the best of the best to Hong Kong, and win. We will provide financial support to non-profit-making scientific research institutions to enable them to establish a local presence in these two clusters. We hope that they will promote collaboration among overseas and local universities and scientific research institutions to do more midstream and downstream R&D projects, and boost our local talent pool. Overseas institutions are most welcome to join these clusters. I am glad to tell you that the HKU, the Institut Pasteur and the HKSTP have signed a Memorandum of Understanding to establish an interdisciplinary research centre for immunology, infection and personalised medicine. It will be one of the first newly formed team within the HKSTP’s healthcare technologies research cluster (Health@Inno Cluster).

These two areas echo Hong Kong’s R&D strengths and capabilities. Hong Kong’s universities remain the prime spawning grounds of innovation in the healthcare/biotechnology/medical fields. Hong Kong’s two medical schools have extensive experience and knowledge in conducting clinical trials, in full compliance with international guidelines for drug registrations. Clinical trials conducted in three Hong Kong hospitals can also be used to support filing new drug applications to the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA), giving Hong Kong a distinct advantage in advancing new medicines for the vast Chinese market. In terms of AI, Hong Kong universities, as a whole, are ranked third globally in terms of citation impact of AI research. In addition, a vibrant cluster of more than 100 biotechnology companies has taken root in the Hong Kong Science Park. Some 300 companies focusing on AI/robotics and data analytics are situated in the Hong Kong Science Park and Cyberport.

One reason behind these new initiatives is our commitment to double Hong Kong’s Gross Domestic Expenditure on Research and Development as a percentage of GDP to 1.5 per cent by 2022. Apart from Government investment, private sector investment and international collaboration are most important. For the first time, to incentivise the private sector to invest more in R&D activities in Hong Kong, a super tax deduction on R&D expenditure has been submitted to our legislature. The scheme aims to provide tax deductions of up to 300 per cent for the first HK$2 million of qualified R&D expenses, and 200 per cent for the remainder. There is no cap on the amount of the relevant tax deduction.

And to propel I&T development, we need to nurture local talents and attract overseas talents. By the end of June, we will launch a pilot fast-track Technology Talent Admission Scheme to enable technology companies/institutes to attract overseas technology talent, in focused technology areas, including biotechnology, artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, robotics, etc. Based on the pilot scheme performance during the first year, we will review the need to increase the scope of this scheme.

In addition, we will launch a $500 million Technology Talent Scheme, including Postdoctoral Hub to provide funding support for enterprises to recruit postdoctoral talent for scientific research and product development. We will also subsidise enterprises to train their staff on high-end technologies.

As I mentioned earlier, Hong Kong is already a world leader in ICT infrastructure. We are also committed to staying ahead and developing Hong Kong into a world-class smart city to improve city management and the quality of our residents’ lives. Last year, we published Hong Kong’s first Smart City Blueprint, setting out our vision and over 70 initiatives, covering six major areas, namely Smart Mobility, Smart Economy, Smart Environment, Smart People, Smart Living and Smart Government.

Hong Kong, where East meets West, remains the international business and cultural centre and international financial centre of Asia. As global economic gravity shifts to Asia, we believe Hong Kong is “The Place to be” for the next wave of innovation and technology development. I have given a comprehensive update on Hong Kong’s I&T developments. I welcome and invite British researchers, entrepreneurs and investors to come and tap the tremendous opportunities here.

Thank you very much. read more