The EU list is a common tool for Member States to tackle external risks of tax abuse and unfair tax competition. It was first conceived in the Commission’s 2016 External Strategy for Effective Taxation, which pointed out that a single EU blacklist would hold much more weight than a medley of national lists and would have a dissuasive effect on problematic third countries. Member States supported the idea, and agreed on the first EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions in December 2017. This list was the result of an extensive screening of 92 jurisdictions, using internationally recognised good governance criteria. The countries that were ultimately blacklisted were those that failed to make a high-level commitment to comply with the agreed good governance standards. Many other countries did commit to comply with the listing criteria within a set deadline (usually the end of 2018). Member States agreed that these countries should be monitored by the Code of Conduct Group and the Commission, to ensure that they delivered fully and on time. The Commission was asked to assess these countries’ progress once the deadline was up, so that Member States could decide on an updated EU list.

What are the main results of the listing process?

The revised list marks the culmination of a long and intensive process of careful analysis and dialogue with third countries steered by the Commission. It confirms the role of the EU as world leader on tax good governance. The clear, credible and transparent process bares fruit: Since December 2017, many of the screened countries have been changing their national laws and tax systems to comply with international standards.

The process is fair with improvements made visible in the list and it boosted transparency with countries’ commitment letters published online. The EU listing process has also created a framework for dialogue and cooperation with the EU’s international partners, to address concerns with their tax systems and discuss tax matters of mutual interest.

In particular, the process has raised the standards of tax good governance globally, both through the positive changes introduced by third countries and through its influence on international criteria for zero-tax countries.

During the last year, many jurisdictions implemented concrete measures to fix problems identified in their tax systems. 60 countries took action on the Commission’s concerns and over 100 harmful regimes were eliminated.

Zero tax countries have introduced new measures to ensure a proper level of economic substance and information exchange.

Over 20 jurisdictions have taken steps to bring their tax transparency standards into line with international norms, and even more should do so by the end of 2019.

Finally, as a result of the EU process, dozens of countries have been brought into international fora such as the OECD’s Global Forum for transparency and the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Inclusive Framework for the first time.

What countries are on the updated EU list of non-cooperative tax jurisdictions, and why?

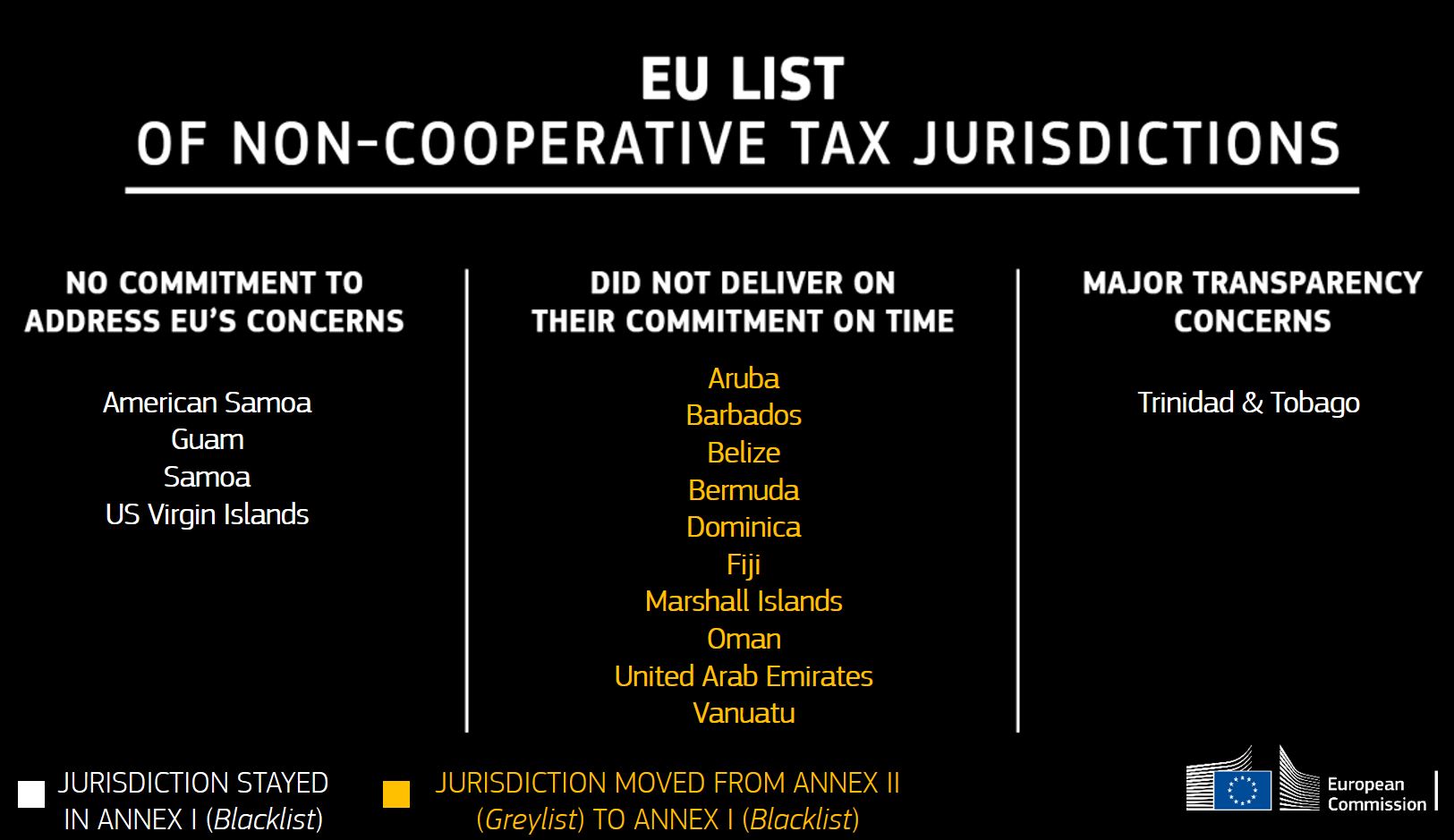

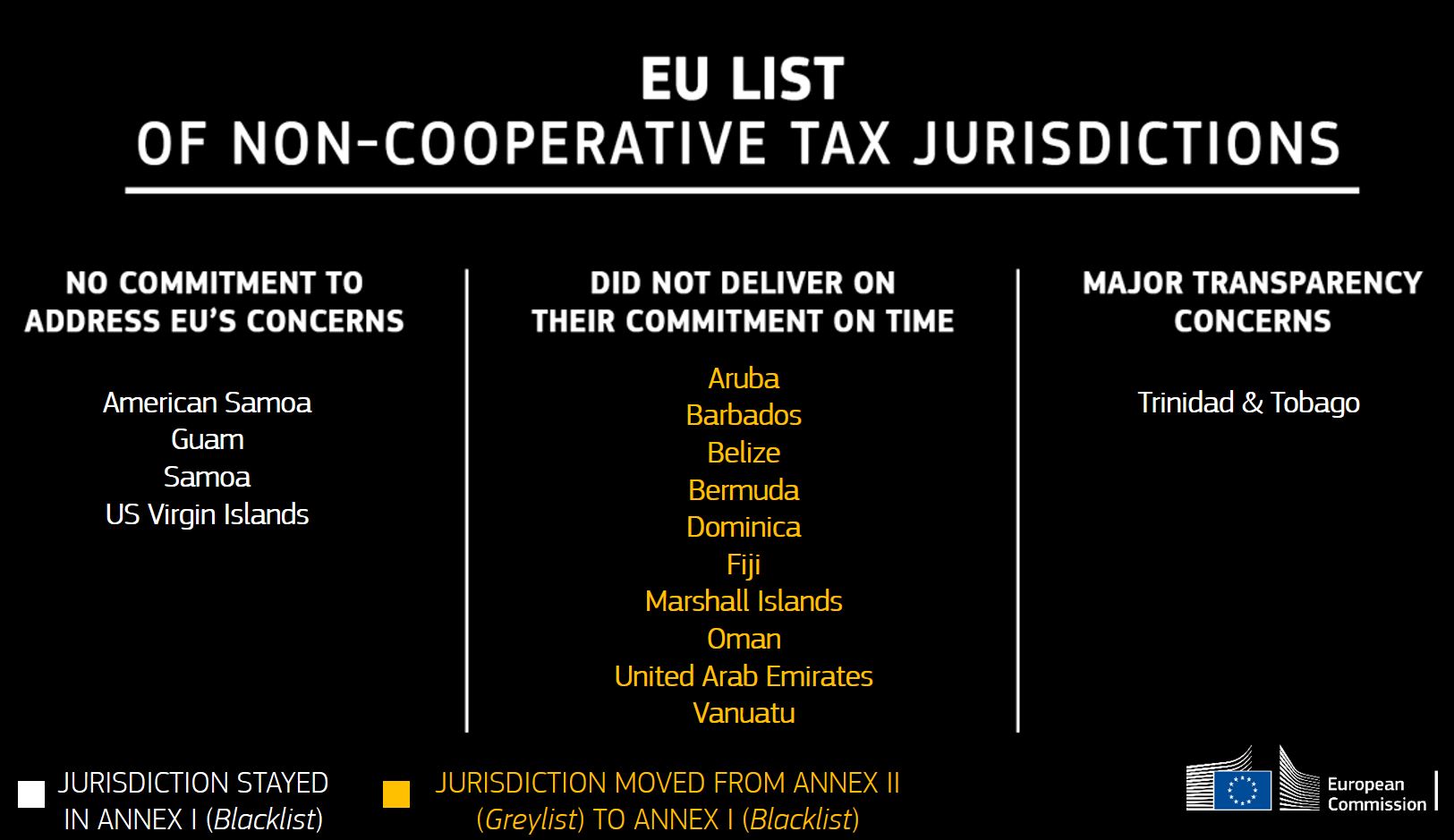

Based on the Commission’s screening, ministers blacklisted today 15 countries. Of those, 5 have taken no commitments since the first blacklist adopted in 2017: American Samoa, Guam, Samoa, Trinidad and Tobago, and US Virgin Islands. 3 others were on the 2017 list but were moved to the grey list following commitments they had taken but had to be blacklisted again for not having followed up: Barbados, Unites Arab Emirates and Marshall Islands. A further 7 countries were moved from the grey list to the blacklist for the same reason: Aruba, Belize, Bermuda, Fiji, Oman, Vanuatu and Dominica.

Another 34 jurisdictions have already taken many positive steps to comply with the requirements under the EU listing process, but should complete this work by the end of 2019, to avoid being blacklisted next year. The Commission will continue to monitor their progress closely. These countries are: Albania, Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Armenia, Australia, Bahamas, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, British Virgin Islands, Cabo Verde, Costa Rica, Curacao, Cayman Islands, Cook Islands, Eswatini, Jordan, Maldives, Mauritius, Morocco, Mongolia, Montenegro, Namibia, North Macedonia, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Serbia, Seychelles, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, and Vietnam.

Following the commitments in 2017, many countries have now delivered the reforms and improvements that they promised, and 25 countries from the original screening process have now been cleared: Andorra, Bahrain, Faroe Islands, Greenland, Grenada, Guernsey, Hong Kong, Isle of Man, Jamaica, Jersey, Korea, Liechtenstein, Macao SAR, Malaysia, Montserrat, New Caledonia, Panama, Peru, Qatar, San Marino, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Taiwan, Tunisia, Turks and Caicos, and Uruguay.

How is the EU list of non-cooperative tax jurisdictions compiled?

The EU list of non-cooperative tax jurisdictions is composed of countries that either failed to deliver on their commitments to comply with required good governance criteria, or did not commit to do so at all.

Many other jurisdictions made a high-level commitment to comply with the criteria for transparency and fair taxation under the EU listing process, and remained under monitoring as a result. Most of these countries had until 31 December 2018 to deliver on their commitments, although 8 developing countries without a financial centre were given an extra year for certain criteria.

The Commission monitored the progress of the countries throughout 2018 and reported on any new developments to Member States in the Code of Conduct Group. It also liaised closely with the OECD, taking on board its assessments of countries’ transparency standards and tax regimes, as part of the monitoring process.

The Commission then had to assess whether or not the jurisdictions had adequately fulfilled their commitments by the end of 2018 deadline. On this basis, the Code of Conduct Group recommended an updated EU list of non-cooperative tax jurisdictions, for EU Finance Ministers to endorse.

What are the criteria used in EU listing process?

The EU listing criteria are aligned with international standards and reflect the good governance standards that Member States comply with themselves. These are:

- Transparency: The country should comply with international standards on automatic exchange of information and information exchange on request. It should also have ratified the OECD’s multilateral convention or signed bilateral agreements with all Member States, to facilitate this information exchange. Until June 2019, the EU only requires two out of three of the transparency criteria. After that, countries will have to meet all three transparency requirements to avoid being listed.

- Fair Tax Competition: The country should not have harmful tax regimes, which go against the principles of the EU’s Code of Conduct or OECD’s Forum on Harmful Tax Practices. Those that choose to have no or zero-rate corporate taxation should ensure that this does not encourage artificial offshore structures without real economic activity. They should therefore introduce specific economic substance requirements and transparency measures.

- BEPS implementation: The country must have committed to implement the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) minimum standards. From 2019, jurisdictions are being monitored on the implementation of these minimum standards, starting with Country-by-Country Reporting.

Who was responsible for monitoring the countries and updating the EU list?

The listing process is managed by the Code of Conduct Group for Business Taxation, based on an intense process of analysis and dialogue steered by the Commission.

In 2018, the Commission monitored the steps taken by the third countries to comply with their commitments under the EU listing process. It analysed the measures taken, to ensure that they were fully compliant, and gave regular progress reports to the Code of Conduct. The Commission also liaised closely with the OECD, to ensure that the EU and international work was as aligned as possible and to receive updates on the OECD’s assessment of certain jurisdictions.

Based on assessments provided by the Commission, the Code of Conduct Group decides whether a jurisdiction should be listed or not, and makes a recommendation to EU Finance Ministers.

Did the third countries have a chance to present their case?

Yes. The Commission is determined that the EU listing process must be as fair, transparent and credible as possible. It has given high priority to ensuring that the relevant countries understood the process and could seek clarifications and technical advice, whenever needed.

Over the course of 2018, the Commission has had extensive contacts with the jurisdictions concerned, at technical, political and diplomatic levels. The Chair of the Code of Conduct Group also engaged openly and constructively with the jurisdictions, on behalf of the Member States. In addition, the Commission and EEAS visited many of the jurisdictions and regions concerned, to allow for face-to-face dialogue on the EU listing process.

At every stage, the jurisdictions were encouraged to engage with the EU, provide any relevant information and seek any clarifications needed. Each country had a chance to present their position, address concerns and discuss how to deepen their cooperation with the EU on tax matters. The Commission relayed any feedback or information from the jurisdictions to the Code of Conduct Group, for input into the final decision.

Why were some countries given more time to deliver on their commitments?

In certain specific cases, Member States agreed to give more time to jurisdictions that could not meet the 2018 deadline to complete their reforms, subject to strict conditions. This was the case for:

- Countries with regimes for non-highly mobile activities, such as manufacturing activities. The conditions for a deadline extension were that the jurisdiction took tangible steps to launch the reform and publically announced it with a clear date of delivery.

- Countries with constitutional/institutional constraints, such as a lack of government, which prevented them from adopting the required reforms within the deadline. In these cases, the deadline was only extended if the jurisdictions in question provided credible proof of their constitutional constraint, shared acceptable draft legislation and gave a clear timeline to complete their reforms.

Developing countries without a financial centre had already been given a longer timeframe (until end of 2019) to deliver on their commitments for the transparency and anti-BEPS criteria.

What sanctions will apply to the blacklisted countries?

At EU level, the Commission has put in place and proposed new measures which will ensure that the EU list has a real impact.

First, the EU list is now linked to EU funding under new provisions in the Financial Regulation and in the European Fund for Sustainable Development (EFSD), the European Fund for Strategic Investment (EFSI) and the External Lending Mandate (ELM). Funds from these instruments cannot be channelled through entities in listed countries.

Second, there is a direct link to the EU list in other relevant legislative proposals. For example, under the new EU transparency requirements for intermediaries, a tax scheme routed through an EU listed country will be automatically reportable to tax authorities. The public Country-by-Country reporting proposal also includes stricter reporting requirements for multinationals with activities in listed jurisdictions. The Commission is examining legislation in other policy areas, to see where further consequences for listed countries can be introduced.

In addition to the EU provisions, Member States agreed on sanctions to apply at national level against the listed jurisdictions. These include measures such as increased monitoring and audits, withholding taxes, special documentation requirements and anti-abuse provisions. The Commission is urging Member States to step up their efforts to agree on strong, binding and coordinated defensive measures, as soon as possible, to give the EU list an even greater impact.

How can a country be de-listed by the EU?

A country will be removed from the list once it has addressed the issues of concern for the EU and has brought its tax system fully into line with the required good governance criteria. The Code of Conduct is responsible for updating the EU list and recommending countries for de-listing to the Council.

Is the EU list in line with the international agenda for tax good governance?

Yes, the EU list firmly supports the international tax good governance agenda. The EU listing criteria reflect internationally agreed standards and countries were encouraged to meet these standards to avoid being listed. The EU also took on board OECD assessments of countries’ transparency standards and tax regimes, as part of the monitoring process. The Commission and Member States were in close and regular contact with the OECD throughout the listing process, to ensure that EU and international work in this area remained complementary.

The EU and international good governance agendas are mutually reinforcing. For example, the OECD has recently integrated the criterion for zero-tax jurisdictions, which was first developed for the EU listing process, into the international tax good governance standards. This will ensure that countries with no or very low corporate taxation do not facilitate companies shifting their profits offshore without any economic substance.

Will the exercise be extended to more countries in the future?

Yes. In 2018, Member States agreed to extend the scope of the screening and monitoring process for the EU list. They decided to start with the G20 countries that were not yet covered, namely Russia, Mexico and Argentina. These countries will be screened in 2019 to see if there are any deficiencies in their tax systems, and will be asked to commit to address them if there are. Other countries will be brought into the scope from 2020 onwards.

More information in the press release.