What has been agreed today?

The European Commission and the United Kingdom’s negotiators have reached an agreement on the entirety of the Withdrawal Agreement of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community, as provided for under Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union.

The Withdrawal Agreement establishes the terms of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. It ensures that the withdrawal will happen in an orderly manner, and offers legal certainty once the Treaties and EU law will cease to apply to the UK.

The Withdrawal Agreement covers the following areas:

- Common provisions, setting out standard clauses for the proper understanding and operation of the Withdrawal Agreement.

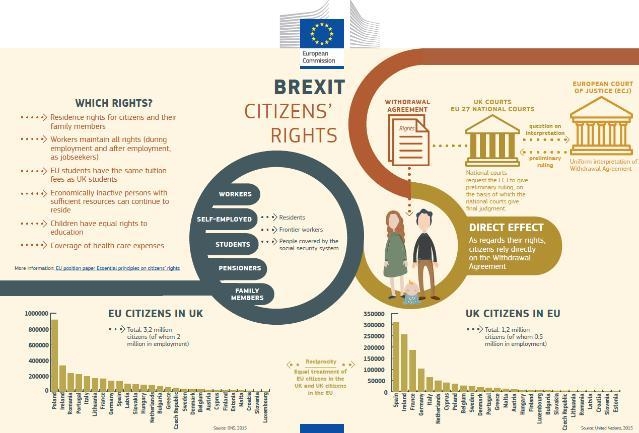

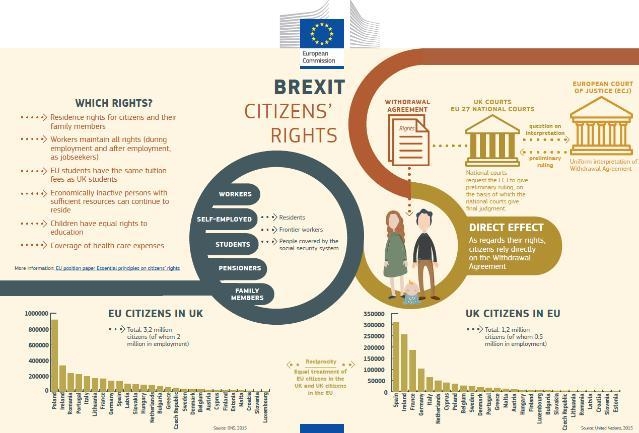

- Citizens’ rights, protecting the life choices of over 3 million EU citizens in the UK, and over 1 million UK nationals in EU countries, safeguarding their right to stay and ensuring that they can continue to contribute to their communities.

- Separation issues, ensuring a smooth winding-down of current arrangements and providing for an orderly withdrawal (for example, to allow for goods placed on the market before the end of the transition to continue to their destination, for the protection of existing intellectual property rights including geographical indications, the winding down of ongoing police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters and other administrative and judicial procedures, the use of data and information exchanged before the end of the transition period, issues related to Euratom, and other matters).

- A transition period, during which the EU will treat the UK as if it were a Member State, with the exception of participation in the EU institutions and governance structures. The transition period will help in particular administrations, businesses and citizens to adapt to the withdrawal of the United Kingdom.

- The financial settlement, ensuring that the UK and the EU will honour all financial obligations undertaken while the UK was a member of the Union.

- The overall governance structure of the Withdrawal Agreement,ensuring the effective management, implementation and enforcement of the agreement, including appropriate dispute settlement mechanisms.

- The terms of a legally operational backstop to ensure that there will be no hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. The protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland also contains UK commitments not to diminish rights set out in the Good Friday (Belfast) Agreement 1998, and to protect North-South cooperation. It provides for the possibility to continue the Common Travel Area arrangements between Ireland and the UK, and preserves the Single Electricity Market on the island of Ireland.

- A protocol on the Sovereign Base Areas (SBA) in Cyprus, protecting the interests of Cypriots who live and work in the Sovereign Base Areas following the UK’s withdrawal from the Union.

- A Protocol on Gibraltar, which provides for close cooperation between Spain and the UK in respect of Gibraltar on the implementation of citizens’ rights provisions of the Withdrawal Agreement, and concerns administrative cooperation between competent authorities in a number of policy areas.

A timeline of events leading to today’s agreement

On 29 March 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May notified the European Council of the UK’s intention to withdraw from the European Union (Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union). Her letter to Donald Tusk, the President of the European Council, formally began the process of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU.

According to Article 50(2) of the Treaty on European Union, the Union shall negotiate and conclude with the United Kingdom the agreement setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal, taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union.

Negotiations on the terms of the UK’s withdrawal began on 19 June 2017, shortly after the UK’s general election. It was agreed that the negotiations would first address the most crucial areas of uncertainty stemming from the UK’s withdrawal: the protection of citizens’ rights after Brexit, the financial settlement, and the question of avoiding a hard border on the island of Ireland. As set out in the European Council (Article 50) guidelines of 29 April 2017, “sufficient progress” was required on these withdrawal issues before discussing the framework for the future EU-UK relationship.

On 8 December 2017, the EU and the UK published a Joint Report, setting out the areas of agreement between both sides on those three withdrawal issues and some other separation issues. This was accompanied by a Communication by the European Commission providing an assessment of the state of progress of the negotiations.

On 28 February 2018, the European Commission published a draft Withdrawal Agreement between the European Union and the United Kingdom, translating into legal terms the December Joint Report. On 19 March 2018, the European Commission and the United Kingdom published an amended version of the draft Withdrawal Agreement highlighting areas of agreement and disagreement using a green, yellow and white colour-coding.

Also on 19 March 2018, Prime Minister May reiterated in a letter to President Tusk her commitment to have a legally operative backstop solution in the Withdrawal Agreement to avoid a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. The European Council (Article 50) in March agreed with the UK’s proposal to have a transition period, and adopted guidelines on the framework for the future relationship.

On 19 June 2018, a Joint Statement was published, outlining further progress in the negotiations on the Withdrawal Agreement.

On 14 November 2018, the European Commission and UK negotiators reached an agreement on the entirety of the Withdrawal Agreement and on an outline of the political declaration on the future EU-UK relationship.

How were the negotiations conducted?

The Agreement has been negotiated in the light of the European Council guidelines and in line with the negotiating directives of the Council.

Throughout the negotiations, the European Commission has ensured an inclusive process with regular meetings with the 27 EU Member States at different levels. The European Commission has also been in close and regular contact with the European Parliament to ensure that its views and positions are duly taken into account. Additional input from the EU consultative bodies and stakeholders has helped the European Commission gather evidence of the EU-wide impact of the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the EU.

The negotiations have been carried out with unprecedented transparency. The European Commission has published negotiating documents which have been shared with EU Member States, the Council of the European Union, the European Parliament, and the United Kingdom, as well as European Council guidelines, essential principles papers defining the EU’s negotiating positions, and all other relevant documents. These documents are available on the European Commission’s website on the negotiations.

This part sets out the necessary clauses to ensure the correct understanding, operation and interpretation of the Withdrawal Agreement. They provide the basis for the correct application of the Agreement. From the outset of the negotiations, the EU has attached great importance to the fact that the provisions of the Withdrawal Agreement must clearly have the same legal effects in the UK as in the EU and its Member States.

The Agreement explicitly includes such a requirement, meaning that both Parties should ensure in their respective legal orders primacy and direct effect, as well as consistent interpretation with the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) handed down until the end of the transition. Direct effect is mentioned explicitly with reference to all provisions of the Withdrawal Agreement which meet the conditions of direct effect under Union law. This basically means that concerned parties can invoke the Withdrawal Agreement directly before national courts both in the UK, as well as in the EU Member States.

It is also mandatory for the purposes of interpreting the Agreement to use the methods and general principles of interpretation applicable within the EU. This covers, for instance, the obligation to interpret the concepts or provisions of Union law referred to in the Withdrawal Agreement in a manner consistent with the Charter of Fundamental Rights.

Furthermore, UK courts must abide by the principle of consistent interpretation with the CJEU case law handed down until the end of the transition period and pay due regard to CJEU case law handed down after that date.

The Agreement specifically requires the UK to ensure compliance with the above through primary domestic legislation, specifically empowering UK judicial and administrative authorities to disapply inconsistent or incompatible national law.

This section also makes clear that references to Union law in the Withdrawal Agreement shall be understood as including amendments made until the last day of the transition period. Few exceptions are foreseen, notably for specific financial settlement provisions, to avoid imposing additional obligations on the UK, and for the transition period, during which Union law will continue to apply dynamically to and in the UK. They shall be understood also as including the acts supplementing or implementing referenced provisions.

Finally, the Agreement provides that the UK shall be disconnected at the end of the transition period from all EU databases and networks, unless specifically provided otherwise.

II. What has been agreed on citizens’ rights?

The right for every EU citizen and their family members to live, work or study in any EU Member State is one of the foundations of the European Union. Many EU and UK citizens have made their life choices based on rights related to free movement under Union law. Protecting the life choices of those citizens and their family members has been the first priority from the beginning of the negotiation.

The Withdrawal Agreement safeguards the right to stay and continue their current activities for over 3 million EU citizens in the UK, and over 1 million UK nationals in EU countries.

Who is protected by the Withdrawal Agreement?

The Withdrawal Agreement protects those EU citizens who were residing in the UK and UK nationals who were residing in one of the 27 EU Member States at the end of the transition period, where such residence is in accordance with EU law on free movement.

The Withdrawal Agreement also protects the family members that are granted rights under EU law (current spouses and registered partners, parents, grandparents, children, grandchildren and a person in an existing durable relationship), who do not yet live in the same host state as the Union citizen or the UK national, to join them in the future.

Children will be protected by the Withdrawal Agreement, wherever they are born before or after the UK’s withdrawal, or whether they are born inside or outside the host state where the EU citizen or the UK national resides. The only exception foreseen concerns children born after the UK’s withdrawal and for which a parent not covered by the Withdrawal Agreement has sole custody under the applicable family law.

Which rights are protected?

The Withdrawal Agreement enables both EU citizens and UK nationals, as well as their respective family members, to continue to exercise their rights derived from Union law in each other’s territories, for the rest of their lives, where those rights are based on life choices made before the end of the transition period.

Union citizens and UK nationals, as well as their respective family members can continue to live, work or study as they currently do under the same substantive conditions as under Union law, benefiting in full from the application of the prohibition of any discrimination on grounds of nationality and of the right to equal treatment compared to host state nationals. The only restrictions which apply are those derived from Union law or as provided for under the Agreement. The Withdrawal Agreement does not prevent the UK or Member States from deciding to grant more generous rights.

Residence rights

The substantive conditions of residence are and will remain the same as those under current EU law on free movement. In the case where the host states opted for a mandatory registration system, decisions for granting the new residence status under the Withdrawal Agreement will be made based on objective criteria (i.e. no discretion), and on the basis of the exact same conditions set out in the Free Movement Directive (Directive 2004/38/EC): Articles 6 and 7 confer a right of residence for up to five years on those who work or have sufficient financial resources and sickness insurance, Articles 16 – 18 confer a right of permanent residence on those who have resided legally for five years.

In essence, EU citizens and UK nationals meet these conditions if they are: workers or self-employed; or have sufficient resources and sickness insurance; or are family members of some other person who meets these conditions; or have already acquired the right of permanent residence and are therefore no longer subject to any conditions.

The Withdrawal Agreement does not require physical presence in the host state at the end of the transition period – temporary absences that do not affect the right of residence and longer absences that do not affect the right of permanent residence are accepted.

Those protected by the Withdrawal Agreement who have not yet acquired permanent residence rights – if they have not lived in the host state for at least five years – will be fully protected by the Withdrawal Agreement, and will be able to continue residing in the host state and acquire permanent residence rights also after the UK’s withdrawal.

EU citizens and UK nationals arriving in the host state during the transition period will enjoy exactly the same rights and obligations under the Withdrawal Agreement as those who arrived in the host state before 30 March 2019. Their rights will be subject to the same restrictions and limitations, too. The persons concerned will no longer be beneficiaries of the Withdrawal Agreement if they are absent from their host state for more than five years.

Rights of workers and self-employed persons, and recognition of professional qualifications

The persons covered by the Withdrawal Agreement will have the right to take up employment or to carry out an economic activity as a self-employed person. They will also keep all their workers’ rights based on Union law. For example, they will maintain the right not to be discriminated against on ground of nationality as regards employment, remuneration and other conditions of work and employment; the right to take up and pursue an activity in accordance with the rules applicable to the nationals of the host state, the right to employment assistance under the same conditions as the nationals of the host state, the right to equal treatment in respect of conditions of employment and work, the right to social and tax advantages, collective rights, and the right for their children to access education.

The Withdrawal Agreement will also protect the rights of frontier workers or frontier self-employed persons in the countries where they work.

Additionally, when a person covered by the Withdrawal Agreement who had his or her professional qualifications recognised in the country (an EU Member State or the UK) where he or she currently resides or, for frontier workers, where he or she works, will be able to continue to rely on the recognition decision there for the purpose of carrying out the professional activities linked to the use of those professional qualifications. If he or she has already applied for the recognition of his or her professional qualifications before the end of the transition period, his or her application will be processed domestically in accordance with the EU rules applicable when the application was made.

Social security

The Withdrawal Agreement provides for rules on social security coordination in relation to the beneficiaries of the citizens’ part of the Withdrawal Agreement, and to other persons who at the end of the transition period are in a situation involving both the United Kingdom and a Member State from the social security cooperation perspective.

Those persons will maintain their right to healthcare, pensions and other social security benefits, and if they are entitled to a cash benefit from one country, they may be able to receive it even if they decide to live in another country.

The social security provisions of the Withdrawal Agreement will address the rights of EU citizens and UK nationals in social security cross-border situations involving the UK and (at least) one Member State at the end of the transition period.

Those provisions can be extended to cover “triangular” social security situations involving a Member State (or several Member States), the UK and an EFTA country (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland). This will allow the rights of EU citizens, UK nationals as well as EFTA country citizens who are in that type of triangular situations to be protected.

For this to be operational, three different agreements need to be applicable: an article in the Withdrawal Agreement protecting EFTA nationals, provisions protecting EU citizens in corresponding agreements between the UK and the EFTA countries, and provisions protecting UK nationals in corresponding agreements between the EU and the EFTA countries.

Only if the two latter agreements are concluded and applicable, the article in the Withdrawal Agreement protecting EFTA nationals will be applicable as well. The decision on the applicability of this article will be taken by the Joint Committee created by the Withdrawal Agreement.

Some specific cases covered by the Withdrawal Agreement

Case 1: Workers. You are an EU citizen who arrived in the UK two years ago, and you work in a local hospital. You will be allowed to stay in the UK after the UK leaves the EU. EU free movement law will continue to apply until the end of the transition period. Afterwards, the Withdrawal Agreement provides that, if you are residing in the UK at the end the transition period, you will be able to stay in the UK under essentially the same substantive conditions required by EU free movement law: you will continue to have residence rights if you continue to work (or if you involuntarily stop working in accordance with Article 7(3) of the Free Movement Directive), become self-employed, or become a self-sufficient person (i.e. you have sufficient financial resources and sickness insurance).

However, to this effect you will need to make an application to the UK authorities for a new UK residence status. Once you have accumulated five years of legal residence in the UK, you will be able to apply for your residence status in the UK to be upgraded to a permanent residence status that offers more rights and better protection.

Case 2: Frontier workers relying on professional qualifications. You are a British physiotherapist living in Belgium and working as a physiotherapist in the Netherlands, where you had your British professional qualifications recognised before the end of the transition period. EU free movement law will continue to apply until the end of the transition period. If you are still in the same situation, the Withdrawal Agreement provides that you will be able to continue residing in Belgium and carrying out your professional activities in the Netherlands as a frontier worker or, as applicable, a frontier self-employed person. You will be able to continue relying on the decision taken by the Dutch authorities to recognise your professional qualifications for the purpose of carrying out your professional activities.

Case 3: Students. You are citizen from an EU Member State, and you are currently in the United Kingdom for your studies. EU free movement law will continue to apply until the end of the transition period. Afterwards, if you are still studying in the UK at the end of the transition period, you will be able to stay in the United Kingdom – but you must apply for the new UK residence status. After five years of residence you will be able to apply for a new UK permanent residence status. Moreover, you will continue to be able to ‘switch’ status: you will be able to start working or become a self-employed person.

Applicable procedures

The Withdrawal Agreement leaves the choice up to the host state whether to require or not a mandatory application as a condition for the enjoyment of the rights under the Withdrawal Agreement. The UK has already expressed the intention to apply a mandatory registration system for beneficiaries of the Withdrawal Agreement. Those fulfilling the conditions will be issued with a residence document (which may be in electronic form).

Some EU Member States have indicated that they will also apply a mandatory registration system (so-called “constitutive system”). In other Member States, however, UK nationals complying with the conditions set out in the Agreement will automatically become beneficiaries of the Withdrawal Agreement (so-called “declaratory system”). In the latter case, UK nationals will be entitled to request that the host state issues them a residence document attesting that they are beneficiaries of the Withdrawal Agreement.

The EU has attached particular importance to the existence of smooth and simple administrative procedures for the citizens covered by the Agreement to exercise their rights. Only what is strictly necessary and proportionate to determine whether the criteria for lawful residence have been met, can be required, and any unnecessary administrative burdens will be avoided. These requirements are particularly relevant if the host state opts for a mandatory registration system. The costs of such applications must not exceed those imposed on nationals for issuing similar documents. Those already holding a permanent residence document will be able to exchange it for the ‘special status’, free of charge.

Administrative procedures for applications for the ‘special status’ that the UK or Member States will set up under the Withdrawal Agreement must also respect the above-mentioned requirements. Errors, involuntary omissions or non-respect of the deadline to submit the application have to be dealt with under a proportionate approach. The overall objective is to ensure that the process is as clear, simple and non-bureaucratic as possible for the affected citizens.

Implementation and monitoring of the citizens’ rights part of the Withdrawal Agreement

The text of the Withdrawal Agreement on citizens’ rights is very precise, so that it can be relied upon directly by EU citizens in British courts, and by UK nationals in the courts of the Member States. Any national law provisions that are not consistent with the provisions of the Withdrawal Agreement will have to be disapplied.

UK courts will be able to ask for preliminary rulings from the Court of Justice of the EU on the interpretation of the citizens’ part of the Withdrawal Agreement for a period of eight years following the end of the transition period. For questions related to the application for the UK settled status, that eight-year period will start running on 30 March 2019.

The implementation and application of citizens’ rights in the EU will be monitored by the Commission acting in conformity with the Union Treaties. In the UK, this role will be fulfilled by an independent national authority. This Authority will be granted equivalent powers to those of the European Commission to receive and investigate complaints from Union citizens and their family members, to conduct inquiries on its own initiative, and to bring legal actions before UK courts concerning alleged breaches by the administrative authorities of the UK of their obligations under the citizens’ rights part of the Withdrawal Agreement.

The Authority and the European Commission shall inform each other annually through the Joint Committee established by the Withdrawal Agreement of the measures taken to implement and enforce the citizens’ rights under the Agreement. Such information should include in particular the number and nature of complaints treated and any follow up legal action taken.

Presentation of the citizens’ rights

The graph below explains in a concise manner the key terms of the Withdrawal Agreement. The figures used of 3.2 million EU citizens in the UK and 1.2 million UK citizens in the EU are estimates based on 2015 UN and UK figures. Actual numbers may vary.

III. What has been agreed on separation issues?

In agreement with the European Council (Article 50) guidelines, the Withdrawal Agreement, where needed, seeks to ensure an orderly withdrawal and provides the detailed provisions that are needed for the winding down of ongoing processes and arrangements in a number of policy areas.

Goods placed on the market

The Withdrawal Agreement provides that goods lawfully placed on the market in the EU or the UK before the end of the transition period may continue to freely circulate in and between these two markets, until they reach their end-users, without any need for product modifications or re-labelling.

This means that goods that will still be in the distribution chain at the end of the transition period can reach their end-users in the EU or the UK without having to comply with any additional product requirements. Such goods may also be put into service (where provided in the applicable provisions of Union law), and will be subject to continued oversight by the market surveillance authorities of the Member States and the UK.

By way of exception, the movement of live animals and animal products between the Union market and the UK’s market will, as from the end of the transition period, be subject to the applicable rules of the Parties on imports and sanitary controls at the border, regardless of whether they were placed on the market before the end of the transition period.

This is necessary in view of the high sanitary risks associated with such products, and the need for effective veterinary controls when these products, as well as live animals, enter the Union market or the UK market.

Minimising disruption in distribution chains at the end of the transition period

The Withdrawal Agreement ensures that a good that has already been placed on the market can continue to be made available on the UK market and the EU Single Market after the end of the transition period. This applies to all goods within the scope of the freedom of movement of goods as set out in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, such as: agricultural products, consumer products (such as toys, textiles, cosmetics), health products (pharmaceuticals, medical devices), and industrial products such as motor vehicles, marine equipment, machinery, lifts, electrical equipment, construction products, and chemicals.

However, live animals and animal products, such as animal-derived food, will, as from the end of the transition period, have to comply with the EU or the UK’s rules on imports from third countries.

The agreement provides for example that:

A CE-marked X-ray machine sold by an EU-27 manufacturer to a hospital in the UK but not yet shipped or physically delivered before the end of the transition period, can be shipped and delivered to the hospital after that date on the basis of its compliance with applicable requirements at the time it was placed on the market. Hence, no need for re-certification or affixing of new, UK-specific conformity markings or adapting the product to any new product requirement, including the indications to be affixed on the product or the information to be provided with it (product manual, instructions for use and the like).

Likewise, a car produced by a UK manufacturer based on a type-approval granted by the UK authorities and sold to an EU-27 distributor before the end of the transition period, can be shipped to the distributor, further sold to an end-customer, registered and entered into service in any Member State on the basis of its compliance with applicable requirements at the time it was placed on the market.

Ongoing movements of goods from a customs perspective

For customs, VAT and excise purposes, the Withdrawal Agreement ensures that movements of goods which commence before the UK’s withdrawal from the EU Customs Union should be allowed to complete their movement under the Union rules which were in place at the start of the movement.After the end of the transition period, the EU rules will continue to apply for cross-border transactions that started before the transaction period in terms of VAT rights and obligations for taxable persons, such as reporting obligations, payment and refund of VAT.The same approach applies for ongoing administrative cooperation which, together with exchanges of information that started before withdrawal, should be completed under the applicable EU rules.

Protection of intellectual property rights

Under the Withdrawal Agreement, the protection afforded to existing EU unitary intellectual property rights (trademarks, registered design rights, plant variety rights etc.) on the territory of the UK will be maintained. All such protected rights will have to be protected by the UK as national intellectual property rights. The conversion of the EU right into a UK right for the purpose of protection in the UK will be automatic, without any re-examination and will be free of cost. This will ensure the respect of existing property rights in the UK and provide for the requisite certainty in respect of users and right holders.

The EU and the UK have also agreed that the stock of existing EU-approved geographical indications (GIs) will be legally protected by the Withdrawal Agreement unless and until a new agreement applying to the stock of geographical indications is concluded in the context of the future relationship. Such geographical indications are existing intellectual property rights in the UK and the EU today.

The UK will guarantee at least the same level of protection for the existing stock of those geographical indications that currently applies within the EU. This protection will be enforced through domestic UK legislation.

EU-approved geographical indications bearing names of UK origin (e.g. Welsh Lamb) remain unaffected within the EU and therefore continue to be protected in the EU.

More than 3,000 geographical indications to remain protected in the United Kingdom

More than 3,000 geographical indications, such as Parma ham, Champagne, Bayerisches bier, Feta cheese, Tokaj wine, Pastel de Tentúgal, Vinagre de Jerez, are today protected under EU law as sui generis intellectual property rights for the whole EU, including the UK. The withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union will not lead to any loss of those intellectual property rights. The Agreement on geographical indications covers protected designation of origin, protected geographical indications, traditional specialities that are guaranteed and traditional terms for wine. This agreement will also benefit the geographical indications bearing a name of UK origin (e.g. Welsh lamb): they will also obtain protection under UK law in the UK and maintain the existing protection under EU law in the EU.

Geographical indications have an important value for local communities, both economically and culturally. Each indication protected in the EU represents an agricultural, food or drink product with deep local roots, whose protection under EU law has generated significant value for its producers and the local community. The quality, reputation and characteristics of the products are attributable to their geographical origin. Their protection helps maintaining the authenticity of those products, supports rural development and promotes job opportunities in production, processing and other related services.

Ongoing police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters

The Withdrawal Agreement provides for rules on winding down ongoing police and judicial proceedings in criminal matters involving the UK. Any such proceedings should still be completed according to the same EU rules.

Examples: how will police and judicial cooperation work in practice?

A criminal arrested by the UK on the basis of the European Arrest Warrant should be surrendered to the Member State that was searching for this person.

Similarly, a joint investigation team set up by the UK and other Member States should continue its investigations.

In case an authority from an EU Member State receives a UK request to confiscate proceeds of crime before the end of the transition period, this should be executed according to the applicable EU rules.

Ongoing judicial cooperation in civil and commercial matters

The Withdrawal Agreement provides that EU law on international jurisdiction in cross-border civil disputes should continue to apply to legal proceedings instituted before the end of the transition period, and that relevant EU law on recognition and enforcement of judgments should continue to apply in regard of judgments handed down before end of the transition period.

How will ongoing judicial proceedings between companies be dealt with after the end of the transition period?

By way of example, at the end of the transition period litigation may be pending between a Dutch company and a UK company before a UK court.

The responsibility of the UK court for hearing the case is established by EU law. According to the Withdrawal Agreement, after the end of the transition period, the UK court remains competent for hearing that case on the basis of EU law.

In another example, at the end of the transition period, a company may be in legal proceedings against a UK company before a French court.

According to the Withdrawal Agreement, after the end of the transition period, EU law on the recognition and enforcement of judgements continues to apply to the recognition and enforcement, in the UK, of the judgement rendered by the French court.

Use of data and information exchanged before the end of the transition period

During EU membership of the United Kingdom, private and public bodies in the UK have received personal data from companies and administrations in other Member States.

The Withdrawal Agreement provides that, after the end of the transition period, the UK has to continue applying the EU data protection rules to this “stock of personal data”, until the EU has established, by way of a formal, so-called adequacy decision, that the personal data protection regime of the UK provides data protection safeguards which are “essentially equivalent” to those in the EU.

The formal adequacy decision by the EU has to be preceded by an assessment of the data protection regime applicable in the UK. In the case where the adequacy decision were annulled or repealed, data received will remain subject to the same “essentially equivalent” standard of protection directly under the Agreement.

Ongoing public procurement

The Withdrawal Agreement provides legal certainty on public procurement procedures pending before the end of the transition period, which should be completed in accordance with EU law, hence under the same procedural and substantive rules as the ones under which they were launched.

Euratom

According to the Withdrawal Agreement and in regard of its withdrawal from Euratom and the safeguards it warrants, the United Kingdom accepted its sole responsibility for the continued performance of nuclear safeguards and its international commitment to a future regime that provides coverage and effectiveness equivalent to existing Euratom arrangements.

Euratom will transfer to the UK the ownership of equipment and other property in the UK related to safeguards for which it will be compensated at book value.

The Union also notes that the withdrawal means Euratom’s international agreements will no longer apply to the UK and that the UK needs to engage with international partners in that context.

The right of property of Special Fissile Material held in the UK by UK entities will be transferred from Euratom to the UK. Regarding Special Fissile Material held in the UK by EU27 undertakings, the UK has accepted that Euratom rights should continue (e.g. right to approve future sale or transfer of these materials). Both sides agree that ultimate responsibility for spent fuel and radioactive waste remains with the State where it was produced, in line with international conventions and European Atomic Energy Community legislation.

Ongoing Union judicial and administrative procedures

Under the Withdrawal Agreement, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) will remain competent for judicial procedures concerning the UK registered at the CJEU before the end of the transition period, and those procedures should continue until a final binding judgment is given in accordance with Union rules. All stages of proceedings are concerned, including appeals or referrals back to the General Court. This allows for pending cases to reach completion in an orderly way.

While the above solves the issue of pending cases, it will also be possible to bring certain cases concerning the UK before the CJEU for a resolution according to Union rules after the end of the transition period.

The Agreement provides that, within four years from the end of the transition period, the Commission may bring before the CJEU new infringement cases against the UK, concerning breaches of Union law which occurred before the end of the transition period.

Within the same period, the UK may also be brought before the CJEU for non-compliance with an administrative decision of a Union institution or body taken before the end of the transition period or, for certain procedures specifically identified in the Agreement, after the end of the transition period.

The CJEU jurisdiction for these new cases is consistent with the principle that the termination of a Treaty shall not affect any right, obligation or legal situation of the parties created prior to its termination. This ensures legal certainty and a level playing field between the EU Member States and the UK, with respect to situations occurring when the UK was under Union law obligations.

For what concerns administrative procedures, the Withdrawal Agreement provides that pending procedures shall continue to be handled according to Union rules. This concerns procedures on issues such as competition and state aid, which were initiated before the end of the transition period by institutions, offices and agencies of the Union, and which concern the UK or UK natural or legal persons.

In respect of aid granted before the end of the transition period, for a period of four years after the end of the transition period, the European Commission shall be competent to initiate new administrative procedures on State aid concerning the UK. The Commission shall be competent after the end of that four year period for procedures initiated before the end of that period.

The European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) shall be competent to initiate new investigations for a period of four years after the end of transition period for facts that ocurred before the end of the transiton, or for customs debt arising after the end of the transition period. The possibility to launch such new administrative procedures is consistent with the idea that the UK remains fully bound by Union law until the end of the transition period and therefore compliance and a level playing field with the other Member States should be ensured throughout the whole period.

Functioning of the Union’s institutions, agencies and bodies

According to the Withdrawal Agreement,the current Union privileges and immunities should remain in application for activities that took place before the end of the transition period. Both parties will continue to ensure compliance with obligations of professional secrecy. Classified information and other documents obtained whilst the UK was a Member State should retain the same level of protection as before the end of the transition period.

IV. What has been agreed regarding the transition period?

The Withdrawal Agreement provides for a transition period until the end of 2020. The continued application of EU law during this period will give time to national administrations and businesses to prepare for the new relationship. It will also provide the EU and the UK with time to negotiate the future relationship.

The transition period is set to end on 31 December 2020, taking into account the initial request from the UK for a transition period of around two years, and making it coincide with the end of the current long-term EU budget (the Multiannual Financial Framework 2014-2020).

During this period, the entire Union acquis will continue to apply to and in the UK as if it were a Member State. This means that the UK will continue to participate in the EU Customs Union and the Single Market (with all four freedoms) and all Union policies. Any changes to the Union acquis will automatically apply to and in the UK. The direct effect and primacy of Union law will be preserved. All existing Union regulatory, budgetary, supervisory, judiciary and enforcement instruments and structures will apply, including the competence of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

During this transition period, the UK will have to comply with the EU’s trade policy and will continue to be bound by the Union’s exclusive competence, in particular in respect of the Common Commercial Policy.

The UK will remain bound during the transition period by the obligations stemming from all EU international agreements. In the area of trade, this means that third countries keep the same UK market access. During this period, the UK cannot become bound by new agreements on its own in areas of Union exclusive competence unless authorised to do so by the EU.

As of the withdrawal date (i.e. including during the transition period), the UK, having left the EU, will no longer be part of EU decision-making. It will no longer be represented in the EU institutions, agencies and bodies, and persons appointed, nominated, or representing the UK, and persons elected in the UK, will no longer take part in the EU institutions, agencies, and bodies.

Subject to exceptions, the UK will no longer participate in meetings of Member State groups. The UK cannot, during the transition period, act as a “rapporteur” for European authorities (such as conducting a risk assessment for the EU Chemicals Agency) or for Member States (such as assessing the safety and efficacy of a medicine).

The transition period also offers clarity and predictability to interested parties, including international partners, on fisheries, as it extends the applicability of the Common Fisheries Policy (and terms of relevant international agreements) to the UK throughout the transition. The UK shall be bound by the decisions on fishing opportunities until the end of the transition period. It will be consulted at various stages of the annual decision-making process in respect of its fishing opportunities. Upon invitation by the Union and to the extent permitted by the particular forum, the UK may attend international consultations and negotiations in view of preparing its future membership in relevant international fora.

Possible extension of the transition period

The Withdrawal Agreement includes the possibility for the Joint Committee to extend the transition period. This possibility can only be used once and must be decided by the Joint Committee before 1 July 2020.

This provision also offers the opportunity for the UK to request additional time to make sure that a future agreement, including provisions for avoiding a hard border in Ireland, may be reached before the end of the transition period.

The extension can only be done by mutual agreement of the Union and the UK. All other terms agreed in March in respect of the transition will remain applicable. To recall, this means, in short, full application of Union law to the UK and full powers of the Union institutions, including the Court of Justice.

However, during a possible extension of the transition period, the UK will be treated as a third country for the purposes of the future Multiannual Financial Framework as of 2021. For that framework, the UK will be able to participate in EU programmes based on the legal bases for third countries that will be agreed in EU regulations.

Extending the transition period will require a fair financial contribution from the UK to the EU budget, which will have to be decided by the Joint Committee established by the Withdrawal Agreement.

UK’s participation in European foreign and defence policies during the transition period

The Common Foreign and Security Policy will apply to the United Kingdom during the transition period. In particular, the UK will have to implement the Union’s restrictive measures in place or decided during the transition period, or to support EU statements and positions in third countries and international organisations.

The UK will have the possibility to participate in EU military operations and civilian missions established under the Common and Security Defence Policy (CSDP), yet without any leading capacity. For example, the Operation Headquarters of the EU operation fighting piracy, Atalanta, is transferred from Northwood to Rota in Spain.

The UK will have the possibility to participate in projects of Common Foreign and Security Policy Agencies, including the European Defence Agency, but without having any decision-making role.

UK’s participation in Justice and Home Affairs during the transition period

All elements of the Justice and Home Affairs policy will continue to apply to the United Kingdom during the transition period, and the UK will remain bound by EU acts applicable to it upon its withdrawal. It may choose to exercise its right to opt-in/opt-out with regard to measures amending, replacing or building upon those acts.

However, during the transition period the UK will not have the right to opt-in to completely new measures. The EU may nevertheless invite the UK to cooperate in relation to such new measures, under the conditions set out for cooperation with third countries.

What are the consequences for international agreements?

EU international agreements form part of the acquis covered by the transition. But they are peculiar in that this part of the acquis has been established through negotiation and agreement with the EU’s international partners. During the transition period, the UK will be bound by the obligations stemming from all EU international agreements, including multilateral mixed agreements. This means, for example, that third countries will have access to the UK market under the conditions set out in the EU’s trade agreements. This also guarantees the integrity and homogeneity of the EU Single Market and the Customs Union.

The EU will notify the other parties to the international agreements of the consequences of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. This notification should take place after the signature of the Withdrawal Agreement. The notification will cover all international agreements.

The EU will also notify its international partners that during a transition period agreed as part of the Withdrawal Agreement, the UK will be assimilated to a Member State for the purposes of the international agreements, including those agreements that would provisionally apply or enter into force during the transition period.

V. What has been agreed regarding the financial settlement?

The European Council guidelines of 29 April 2017 requested a single financial settlement covering the EU budget, the termination of the United Kingdom’s membership of all bodies or institutions established by the Treaties and the participation of the UK in specific funds and facilities related to the Union policies. The financial settlement agreed covers all these points and settles the accounts.

According to the Withdrawal Agreement, the UK will honour its share of financing all the obligations undertaken while it was a member of the Union, in relation to the EU budget (and in particular the Multi-annual Financial Framework 2014-2020, including for the payments that will happen after the end of the transition period in relation to the closure of the programmes), the European Investment Bank, the European Central Bank, the Facility for Refugees in Turkey, EU Trust Funds, Council agencies and also the European Development Fund.

Against this backdrop, the Commission and the UK negotiators have agreed on a fair methodology to calculate the UK’s obligations in the context of its withdrawal.

The principles underlying the agreed methodology are that:

- no Member State should pay more or receive less because of the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the Union;

- the United Kingdom should pay its share of the commitments taken during its membership; and

- the United Kingdom should neither pay more nor earlier than if it had remained a Member State. This implies in particular that the United Kingdom should pay based on the actual outcome of the budget, i.e. adjusted to implementation.

How much will the UK pay?

The objective of the negotiations was to settle all obligations that will exist on the date of the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union. Therefore, the agreement is not about the amount of the UK’s financial obligation, but about the methodology for calculating it.

Both sides agreed on an objective methodology which allows honouring all joint commitments vis-à-vis the Union budget (2014-2020), including outstanding commitments at the end of 2020 (“Reste à liquider”) and liabilities which are not matched by assets.

The UK will also continue to guarantee the loans made by the Union before its withdrawal and will receive back its share of any unused guarantees and subsequent recoveries following the triggering of the guarantees for such loans.

In addition, the UK agreed to honour all outstanding commitments of the EU Trust Funds and the Facility for Refugees in Turkey. The UK will remain party to the European Development Fund and will continue to contribute to the payments necessary to honour all commitments related to the current 11th EDF as well as the previous Funds.

The UK’s paid-in capital in the European Central Bank will be reimbursed to the Bank of England and the UK will cease to be a member of the ECB. In relation to the European Investment Bank, the UK paid-in capital will be reimbursed between 2019 and 2030 in annual instalments but will be replaced by a (additional) callable guarantee. The UK will maintain a guarantee of the stock of outstanding EIB’s operations from the date of withdrawal until the end of their amortisation.

The UK will also maintain the EIB privileges and immunities (protocol 5 and 7 of the Treaty) for the stock of operations existing at the date of withdrawal.

What does this mean for EU projects & programmes?

All EU projects and programmes will be financed as foreseen under the current Multiannual Financial Framework (2014-2020). This provides certainty to all beneficiaries of EU programmes, including UK beneficiaries, who will continue to benefit from EU programmes until their closure, but not from financial instruments approved after withdrawal.

How do you calculate the UK’s share?

The UK will contribute to 2019 and 2020 budget and its share will be a percentage calculated as if it had remained a Member State. For the obligations post-2020 the share will be established as a ratio between the own resources provided by the UK in the period 2014-2020 and the own resources provided by all Member States (including the UK) in the same period. This means that the British rebate is included in the UK’s share.

What is the UK’s share in EU wealth (assets – buildings and cash)?

EU assets belong to the EU as the EU has its own legal personality and no Member State has any rights to EU assets. However, the UK part of the EU liabilities will be reduced by corresponding assets, because there is no need for financing liabilities which are covered by assets, so there is no need for the UK to finance them.

How long will the UK be paying for?

The UK will be paying until the last long-term liability has been paid. The UK will not be required to pay sooner than if it had remained a member of the EU. The possibility for both sides to agree to some simplification is foreseen.

Will the UK pay the pension liabilities of the EU civil service?

The UK will pay its share of the financing of pensions and other employee benefits accumulated by end-2020. This payment will be made when it falls due as it is the case for the remaining Member States.

What would be the financial implications of an extension of the transition period?

During any extension of the transition period, the UK will be treated as a third country for the purposes of the future Multiannual Financial Framework as of 2021. However, extending the transition period will require a financial contribution from the UK to the EU budget which will have to be decided by the Joint Committee established for the governance of the Withdrawal Agreement.

VI. What has been agreed on the governance of the Withdrawal Agreement?

The Withdrawal Agreement includes the institutional arrangements to ensure the effective management, implementation and enforcement of the agreement, including appropriate dispute settlement mechanisms.

The EU and the UK have agreed on the direct effect and the supremacy of the entire Withdrawal Agreement under the same conditions as those applicable in Union law, as well as the fact that the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) is the ultimate arbiter for matters related to EU law or Union law concepts. This is a necessary guarantee to make sure that Union law is applied in a consistent manner.

Important parts of the Withdrawal Agreement are built on Union law, which is used to make sure that the withdrawal happens in an orderly manner. Therefore, it is all the more important that the same legal effects, methods and principles of interpretation as for Union law apply.

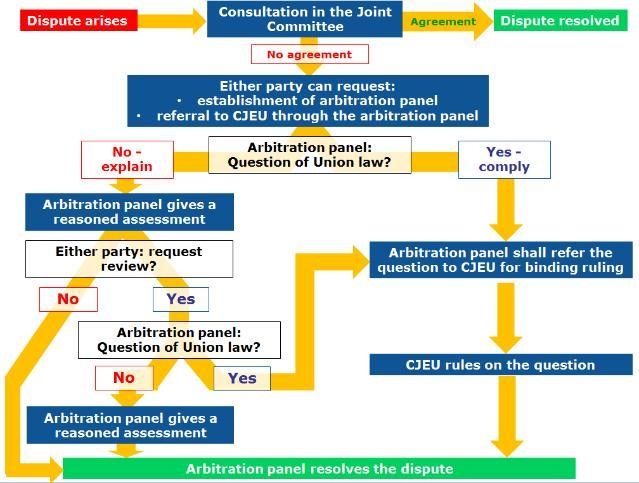

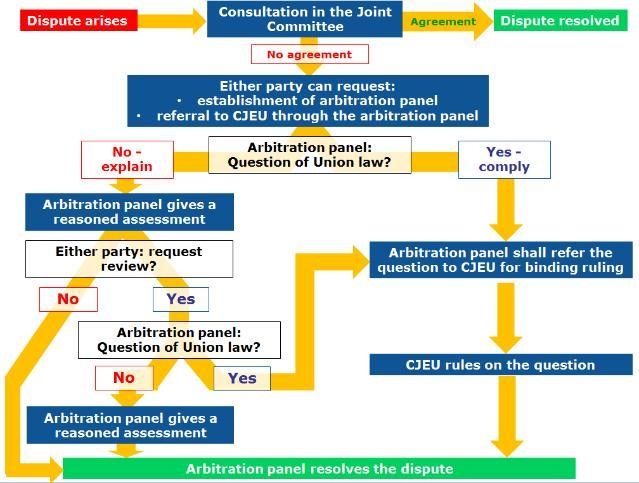

In the event of a dispute on the interpretation of the Withdrawal Agreement, an initial political consultation would take place in a Joint Committee. If no solution is found, either party can refer the dispute to binding arbitration. In those cases where the dispute involves a question of EU law, the arbitration panel has an obligation to refer the question to the CJEU for a binding ruling. In addition, each party may request that the panel refers a question to the CJEU. In such cases, the arbitration panel must refer the question to the CJEU, unless it considers that the dispute in reality does not touch on EU law. It must give the reasons for its assessment and the parties may ask for a review of its assessment.

The decision of the arbitration panel will be binding on the Union and the UK. In case of non-compliance, the arbitration panel may impose a lump sum or penalty payment to be paid to the aggrieved party.

Finally, if compliance is still not restored, the Agreement allows parties to suspend proportionately the application of the Withdrawal Agreement itself, except for citizens’ rights, or parts of other agreements between the Union and the UK. Such suspension is subject to review by the arbitration panel.

VII. Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland

Please refer to the separate document Questions and Answers on the Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland.

VIII. What has been agreed regarding the Sovereign Base Areas in Cyprus?

As outlined in the Joint Statement of 19 June 2018, both the EU and the UK committed to establishing appropriate arrangements for the Sovereign Base Areas, “in particular with the aim to protect the interests of Cypriots who live and work in the SBAs following the UK’s withdrawal from the Union, in full respect of the rights and obligations under the Treaty of Establishment.”

The EU and the UK have agreed on the terms of a Protocol which will give effect to this and which is annexed to the Withdrawal Agreement.

The aim of the Protocol is to ensure that EU law, in the areas stipulated in Protocol 3 to Cyprus’s Act of Accession, will continue to apply in the Sovereign Base Areas, with no disruption or loss of rights especially for the approximately 11,000 Cypriot civilians living and working in the areas of the SBAs. This applies to a number of policy areas such as taxation, goods, agriculture, fisheries and veterinary and phytosanitary rules.

The Protocol confers responsibility on the Republic of Cyprus for the implementation and enforcement of Union law in relation to most of the areas covered, with the exception of security and military affairs.

IX. What has been agreed regarding Gibraltar?

The European Council guidelines of 29 April 2017 set out that “no agreement between the EU and the United Kingdom may apply to the territory of Gibraltar without the agreement between the Kingdom of Spain and the United Kingdom.”

Bilateral negotiations between Spain and the UK have now concluded. A Protocol referring to these bilateral arrangements is annexed to the Withdrawal Agreement.

The Protocol forms a package with bilateral memoranda of understanding between Spain and UK in respect of Gibraltar. This concerns bilateral cooperation on citizens’ rights, tobacco and other products, environment, police and customs matters, as well as a bilateral agreement in relation to taxation and the protection of financial interests.

On citizens’ rights, the Protocol establishes the basis for administrative cooperation between the competent authorities for the implementation of the Withdrawal in relation to people living in the Gibraltar area, and in particular frontier workers.

On air transport law, it establishes the possibility, in case of an agreement between Spain and UK on the use of the Gibraltar airport, to make applicable to Gibraltar during the transition the EU legislation previously not applicable there.

On fiscal matters and protection of financial interests, the Protocol establishes the basis for administrative cooperation between the competent authorities for achieving full transparency in tax matters, fighting against fraud, smuggling, and money laundering. The UK also commits that international standards in this area are complied with in Gibraltar. In relation to tobacco, the UK commits to ratify certain conventions in respect of Gibraltar and to put in place before 31 June 2020 a system of traceability and security measures on cigarettes. In respect of alcohol and petrol, the UK commits to ensure that a tax system which aims at preventing fraud is in force in Gibraltar.

On environment protection and fishing and cooperation in police and customs matters, the Protocol establishes the basis for administrative cooperation between the competent authorities.

A specialised committee is also established for overseeing the application of this Protocol.