The win-win calculus of global family remittances

DUBAI: Irish Basco remembers all the occasions that her father was not around to attend; birthdays, family dinners, graduation ceremonies. He moved to Saudi Arabia 20 years ago when she was seven years old. At the time, the family was growing; working in the Philippines would not have been enough to meet its growing expenses. The solution was to find a job abroad and send money home regularly.

So when Basco’s father packed his bags and flew to the Middle East with a heavy heart, he left behind his wife and three young children who had no idea of the adjustments they would have to go through in the years ahead.

As the world prepares to mark International Day of Family Remittances on June 16, it recognizes the sacrifices made by families such as the Bascos and the difference remittances have made in the lives of those receiving them while playing a major role in the economies of many countries.

The Middle East, especially the Gulf region, is full of stories of migration, separation from loved ones, and remittances. The narrative is as much of economic success as it is of human resilience. Economic migrants form the backbone of a flourishing remittance industry that is only projected to grow.

The UN estimates there are more than 200 million migrants around the world who send money to their home countries, supporting more than 800 million family members, most of whom are in low- to middle-income countries (LMICs).

World Bank data show that in 2018 remittance flows to LMICs reached $529 billion, an increase of 9.6 percent compared to 2017 figures. This is expected to grow this year to $550 billion, making it larger than foreign direct investment and official development assistance flows. According to the bank: “In the coming decades, demographic forces, globalization and climate change will increase migration pressures both within and across borders.”

One expert says the movement of people across international boundaries for work is a natural occurrence in a world where skill sets differ from one country to another.

“There are defined borders in the world, but human beings are transferring from one place to another, so it’s an inherent consequence that they will have to send money to their homeland,” Mahmood Bangara, chairman of the Dubai chapter of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (ICAI), told Arab News.

Global remittances have a lasting impact on the lives of families. Irish Basco, who graduated from a private university in the Philippines in 2013, said she could not have got her degree without her father’s support.

“We can’t deny that we experienced the good side of (migration). My father was able to provide something that the Philippines couldn’t. My father worked in a factory. He pursued different side jobs just to earn more,” she told Arab News by phone from Manila.

“If he hadn’t gone to Saudi Arabia, we wouldn’t have survived. I wouldn’t have been able to finish my education.”

But Basco said her family would never have wanted her father to leave the country “if there had been options other than migrating for work.” She said families are often pushed to the wall by circumstances.

Basco also said her father’s remittances allowed them to make a few investments.

“Expats remit money back home for a number of reasons; to support families, to earn higher rates of interest on local bank deposits, to invest in local real estate, stocks and other assets, to manage inheritance and build retirement funds,” Ambareen Musa, a UAE-based financial expert and CEO of the financial comparison website Souqalmal, told Arab News.

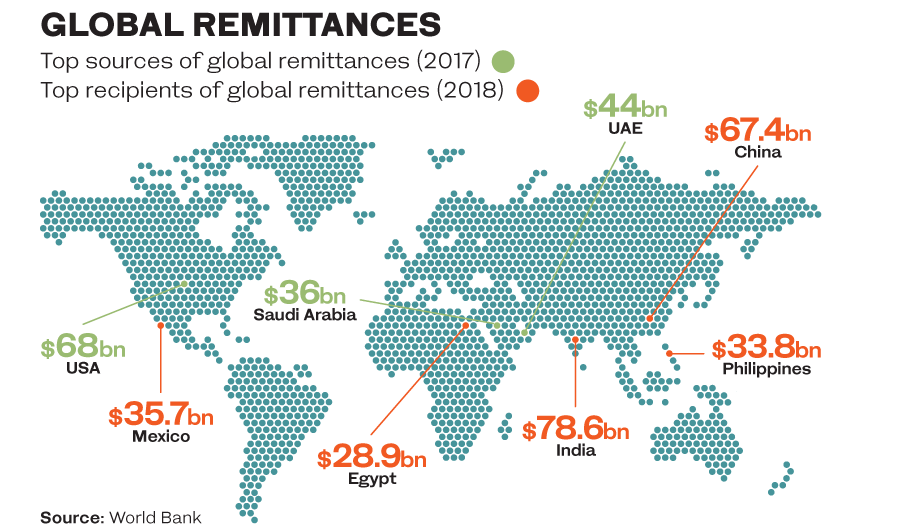

The benefits of remittances go beyond tending to the needs of families. For many developing countries, money derived from overseas transfers make up a significant chunk of their foreign-exchange earnings. “India, China, Mexico, Philippines and Egypt were the biggest remittance recipients in 2018 (in that order),” Musa said, citing World Bank data.

“India received over $78 billion in remittances in 2018, which made up 3 percent of the country’s GDP while the Philippines received over $33 billion, which formed a sizable 10 percent portion of GDP. These countries, like many others, rely on remittances to support their economic growth.”

The ICAI’s Bangara said remittances are a form of income for countries that can be used for domestic consumption.

“They can become savings in the bank. They can be used for certain purposes including investments and property purchases,” he said. “The money benefits the receiving countries by enabling them to meet project expenses. As long it is invested in some form, the money will be available for national development.”

Although the benefits of remittances are more apparent for the receiving countries, the sending countries are also reaping rewards through the services provided by foreign workers who choose to work there, to say nothing of the remittance business itself, which is now a multibillion-dollar, transnational industry.

“Nobody will employ overseas labor to incur losses. Nobody is forced to employ foreign labor,” Bangara said, adding that the remitting countries, such as those of the Gulf, benefit from labor migration in many ways.

As to whether the nationalization programs under way in several Gulf states will affect the prospects of migrant workers and consequently the remittance industry, Bangara said: “The elimination of foreign workforce is not going to happen in the near future.”

“It is true that there is a growing preference for employing domestic labor in almost all countries. But given the growth of these economies, they may continue to need the services of expatriate workers. Employment rates might be slightly affected, but there will be more projects coming up that will drive economic growth and require more manpower.”

It wasn’t easy growing up without a father figure, Basco said. No amount of money can replace a father’s presence, she said. “I feel that even if he finally decides to retire and come home, it will be difficult to get back all those moments,” she said. “But we will try.”

Oman bans expats in certain private higher education jobsExpats welcome Saudi ‘green card’ but say questions need to be answered