Antitrust: Commission publishes final report on e-commerce sector inquiry – frequently asked questions

The European Commission has today published the final report on the competition sector inquiry into e-commerce which was launched in May 2015.The sector inquiry forms part of the Digital Single Market strategy. One of the main goals of this strategy is better access for consumers and businesses to goods and services via e-commerce across the EU.

The e-commerce sector inquiry complements the Commission’s legislative proposals in this regard. The objective of the sector inquiry was to allow the Commission to identify possible competition concerns in European e-commerce markets.

The Commission’s initial findings presented in a preliminary report in September 2016 were largely confirmed by the stakeholder consultation that followed its publication.

Please also see the press release. For more background about the e-commerce sector inquiry and competition sector inquiries in general, please see the factsheet published at the launch of the inquiry and the sector inquiry’s webpage.

- What kind of information has the Commission gathered in the sector inquiry?

The Commission gathered information from nearly 1900 stakeholders from all 28 EU Member States and collected around 8000 distribution and license agreements. The sector inquiry covered e-commerce in consumer goods and digital content.

With respect to consumer goods questionnaires were sent to retailers, manufacturers, e-commerce platforms (marketplaces and price comparison websites) and payment service providers. The following product categories were covered: clothing, shoes and accessories; consumer electronics (including computer hardware); electrical household appliances; computer games and software; toys and childcare articles; books; CDs, DVDs and Blu-ray discs; cosmetic and healthcare products; sports and outdoor equipment; and house and garden.

With respect to digital content, the Commission sent questionnaires to service providers and right holders offering the following types of digital content: films, sports, fiction TV (e.g. drama), children programmes, non-fiction TV (e.g. documentaries), music and news.

The sample of respondents was designed to ensure a broad representation of companies and business models active in e-commerce.

2. What are the main findings in relation to e-commerce of consumer goods?

High degree of price transparency leading to an increase in price competition

Increased online price transparency is the market feature that most affects the behaviour of market players and consumers. 53% of respondent retailers track the online prices of competitors, with almost seven out of ten retailers using automatic software programmes to do so.

Increased direct retail activities by manufacturers

64% of respondent manufacturers opened their own online retail shops in the last 10 years. Cosmetics and healthcare is the product category with the highest proportion of manufacturers with their own online shop. As a result of this trend, in the last decade many manufacturers increasingly compete with their distributors at the retail level.

Expansion of selective distribution

In selective distribution systems, manufacturers select distributors on the basis of a set of specific criteria. These criteria seek to a large extent, both in relation to online and offline sales, to achieve high quality distribution, a coherent brand image and high quality pre- and after-sales services. In the last 10 years, in response to the growth of e-commerce, around one in five respondent manufacturers introduced selective distribution systems for the first time and 67 % of those who use selective distribution introduced new selection criteria, in particular for online sales. Selective distribution is particularly prevalent in some sectors, such as clothing and shoes.

Almost half of the manufacturers using selective distribution reported that they do not allow pure online players to join their selective distribution network.

However, the results of the e-commerce sector inquiry do not appear to question the principles of the Commission’s approach to selective distribution as reflected in the current rules for vertical agreements between companies operating at a different level of the distribution chain. Many selective distribution systems pursue the legitimate aim of ensuring the quality of distribution, a coherent brand image and a high quality of pre- and after-sales services. Such systems therefore typically serve to increase competition on parameters other than price.

More contractual sales restrictions

Manufacturers have also responded to the growth of e-commerce by using contractual sales restrictions regarding the distribution of their products. These restrictions may take various forms, such as pricing restrictions, and restrictions to sell or advertise through certain online channels or to sell cross-border.

Free-riding

Customers can switch swiftly from one sales channel to another. Many of them use the pre-sales services offered by one sales channel (such as product demonstration, personal advice in a brick and mortar shops or search for product information online) but then purchase the product through another sales channel. In such cases the costs of pre-sales services become difficult to recoup (there is “free-riding”). This is a major concern for many manufacturers.

- What are the main contractual sales restrictions that the Commission identified in e-commerce markets of consumer goods?

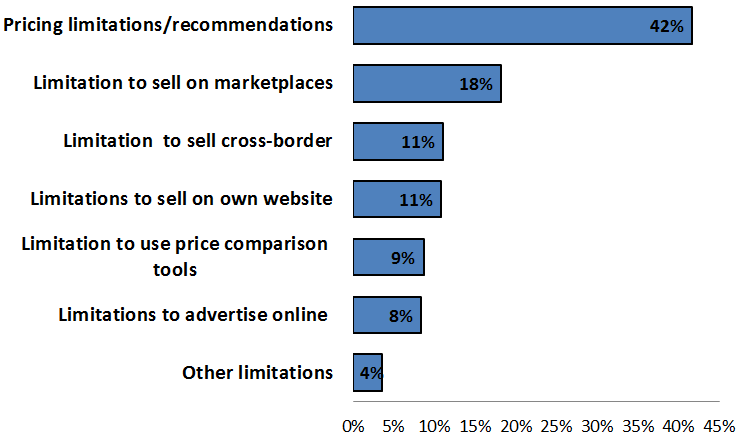

Overall, half of the retailers that replied to the sector inquiry report that they are affected by at least one contractual sales restriction. The figure below provides an overview of the prevalence of certain restrictions among such retailers.

Picture 1:

Share of retailers having contractual restrictions, per type of restriction (retailers may have more than one type of restriction in place)

The following types of contractual restrictions are the most commonly encountered:

(i) Pricing restrictions

Manufacturers and retailers use pricing restrictions/recommendations in response to increased online price competition and, in particular, to the high online price transparency and low search costs for customers. Across the EU, two out of five respondent retailers report experiencing some form of pricing restrictions/recommendations and four out of five respondent manufacturers say that they recommend certain resale prices to their distributors.

Almost a third of respondent retailers confirm that they normally comply with the price indications given by the manufacturers, while slightly more than a quarter say that they never comply. The remaining retailers report that compliance with manufacturers’ pricing indications depend on each specific circumstance.

(ii) Marketplace restrictions

The usage of marketplace restrictions varies across the EU as can be seen from the chart below.

Across the EU, 18 % of retailers report marketplace restrictions in their contracts with suppliers. The Member States with the highest proportion of retailers with marketplace restrictions in their distribution agreements are Germany (32 %) and France (21 %). The Member States with the lowest proportion are Sweden (8 %) and Denmark (6 %). Marketplace restrictions encountered in the sector inquiry range from absolute bans to restrictions on selling on online marketplaces that do not fulfil certain quality criteria.

The results of the sector inquiry show that six out of ten retailers use only their own online shop when selling online. Only4 % of the respondent retailers sell online only via marketplaces. 31 % of retailers use both sales channels when selling online.

The differences between Member States and product categories when it comes to market place restrictions confirm that a case by case assessment of the impact of marketplace restrictions on competition is necessary.

(iii) Cross-border sales restrictions

Over one in ten retailers report that they have contractual cross-border sales restrictions in at least one product category. The product category with the highest proportion of retailers experiencing cross-border sales restrictions is clothing and shoes, followed by consumer electronics.

These contractual cross-border restrictions limit the ability of retailers to serve customers in other Member States and require retailers to apply geo-blocking measures. This means blocking access to websites, re-routing customers to websites targeting other Member States, refusing to deliver cross-border or to accept cross-border payments.

It should be noted that the majority of geo-blocking is based on unilateral business decisions of retailers. Even though only 11% of retailers face contractual limitations on their ability to sell cross-border, in total almost four in ten of them use geo-blocking to restrict cross-border online sales.

iv) Restrictions on the use of price comparison tools

The findings of the sector inquiry show that the use of price comparison tools is widespread with more than a third of retailers reporting that they supplied data feeds to price comparison tool providers.

Around one in ten retailers report that they have agreements with suppliers that contain some form of restriction in their ability to use price comparison tools. The proportion of retailers affected by price comparison tool restrictions is highest in Germany (14 %), Austria (13 %) and the Netherlands (13 %). These price comparison tool restrictions range from absolute bans to restrictions based on certain quality criteria.

4. How does EU competition policy achieve the right balance between the diverging interests of manufacturers, online and ‘bricks-and-mortar’ retailers, marketplaces and ultimately consumers?

Increased online price competition has benefits for consumers. It may however affect competition on parameters other than price, such as quality, brand and innovation. The sector inquiry shows that maintaining high quality distribution (including pre-and post-sale services) is central for manufacturers and brand owners.

EU competition policy/enforcement aims at finding the right balance between the interests of e-commerce businesses and ‘bricks-and-mortar’ distribution. For instance, manufacturers may operate selective distribution networks with a limited number of selected retailers, which have to fulfil certain selection criteria in order to be accepted to the network. Manufacturers can also charge different (wholesale) prices to different retailers in order to level the playing field, which is a normal part of the competitive process. Simultaneously, under EU competition rules, retailers must be able to independently set the resale prices, sell products online on their website and serve customers from outside their territory.

5. What are the main findings in relation to e-commerce in digital content?

Securing attractive digital content is essential for digital content providers that wish to be competitive, as emphasised by virtually all respondents. One of the key determinants of competition in digital content markets is therefore the availability of licences from the holders of the content copyrights.

Online distribution of content and demand for online rights has not dramatically altered the way in which right holders license their rights. Rights tend to be split between:

- technologies (such as the right to transmit online and to deliver the content via a certain technology, such as streaming),

- territories (for example on a national basis), and

- release windows (i.e. concerning certain release periods).

6. What are the main licensing practices that the Commission identified in e-commerce of digital content?

Contractual restrictions in relation to transmission technologies, timing of releases and territories

There are a number of important factors that determine the availability of rights for online distribution of content, such as: (i) the (technological, territorial and temporal) scope of the rights as defined in the licencing agreements between right holders and digital content providers, (ii) the duration of the licencing agreements and (iii) the widespread use of exclusivity, which however is not a competition problem as such.

The results of the sector inquiry show that across the EU, seven out of ten respondent digital content providers report having implemented at least one type of geo-blocking measure. The large majority of respondents are required by rights holders to restrict access to their online digital content services for users from other Member States by means of geo-blocking.

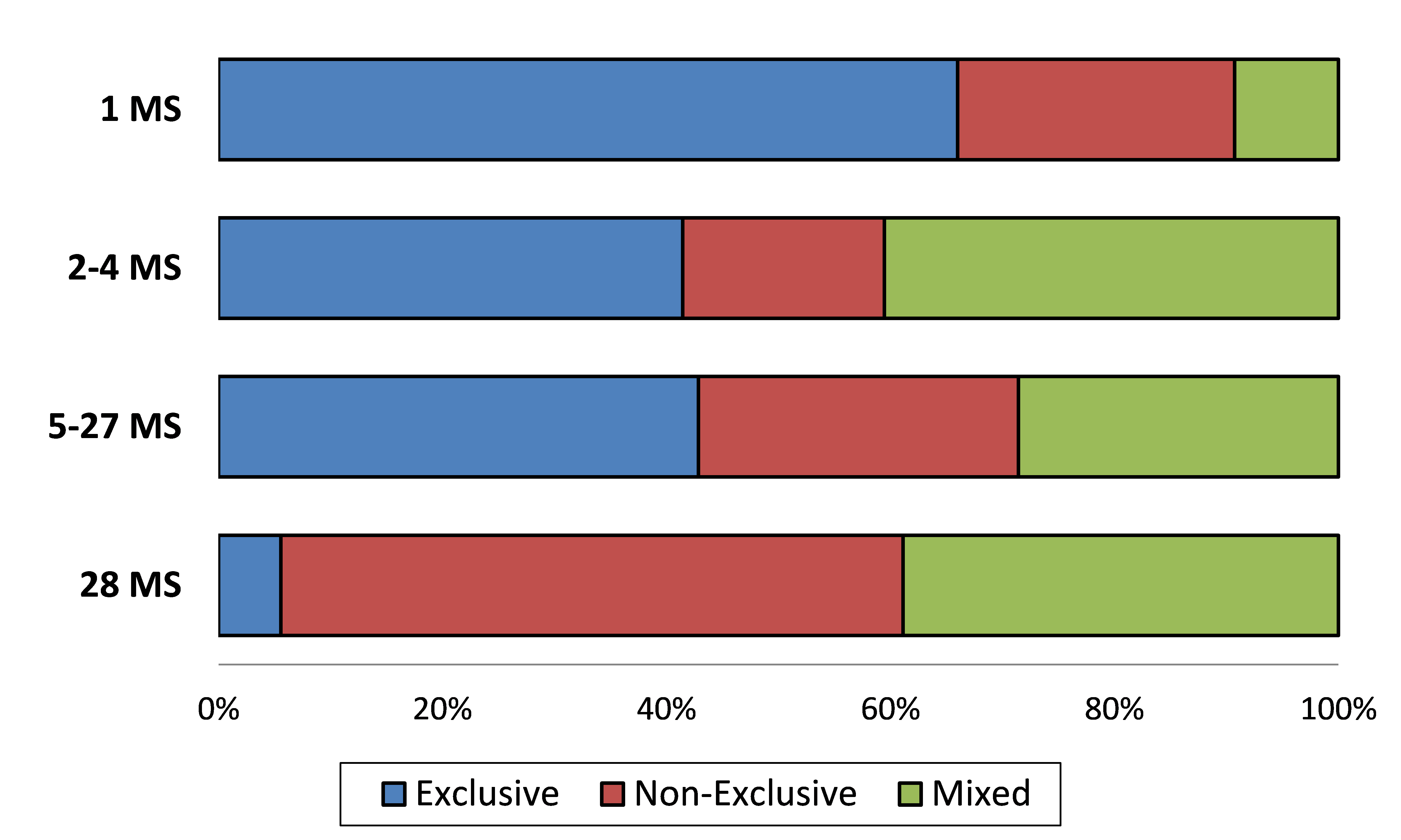

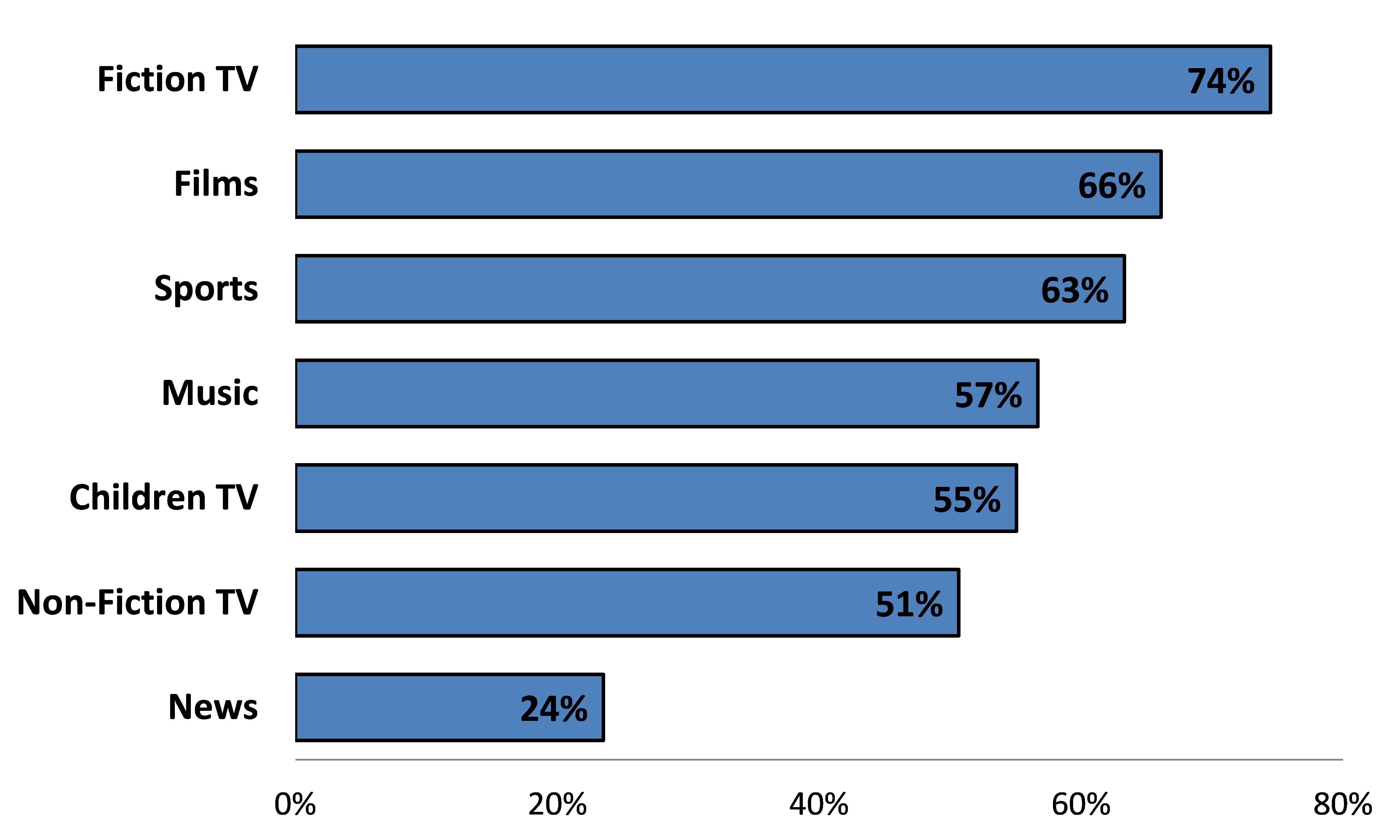

Exclusive agreements and geo-blocking are widespread as can be seen in the charts below.

Content providers can engage in geoblocking for objectively justified reasons, such as to deal with VAT issues or certain public interest legal provisions. The Commission has already proposed legislation to ensure that consumers seeking to buy products and services in another EU country, be it online or in person, are not discriminated against in terms of access to prices, sales or payment conditions, unless this is objectively justified for a specific reason. The Commission has also made proposals on the modernisation of the EU copyright rules. Both proposals are currently being negotiated with the European Parliament and the Council.

Picture 2:

Share of agreements including exclusive/non-exclusive rights licensed for a certain territorial scope – all agreements submitted by right holders

Picture 3:

Share of agreements requiring providers to geo-block by category – Average for all respondents – EU 28

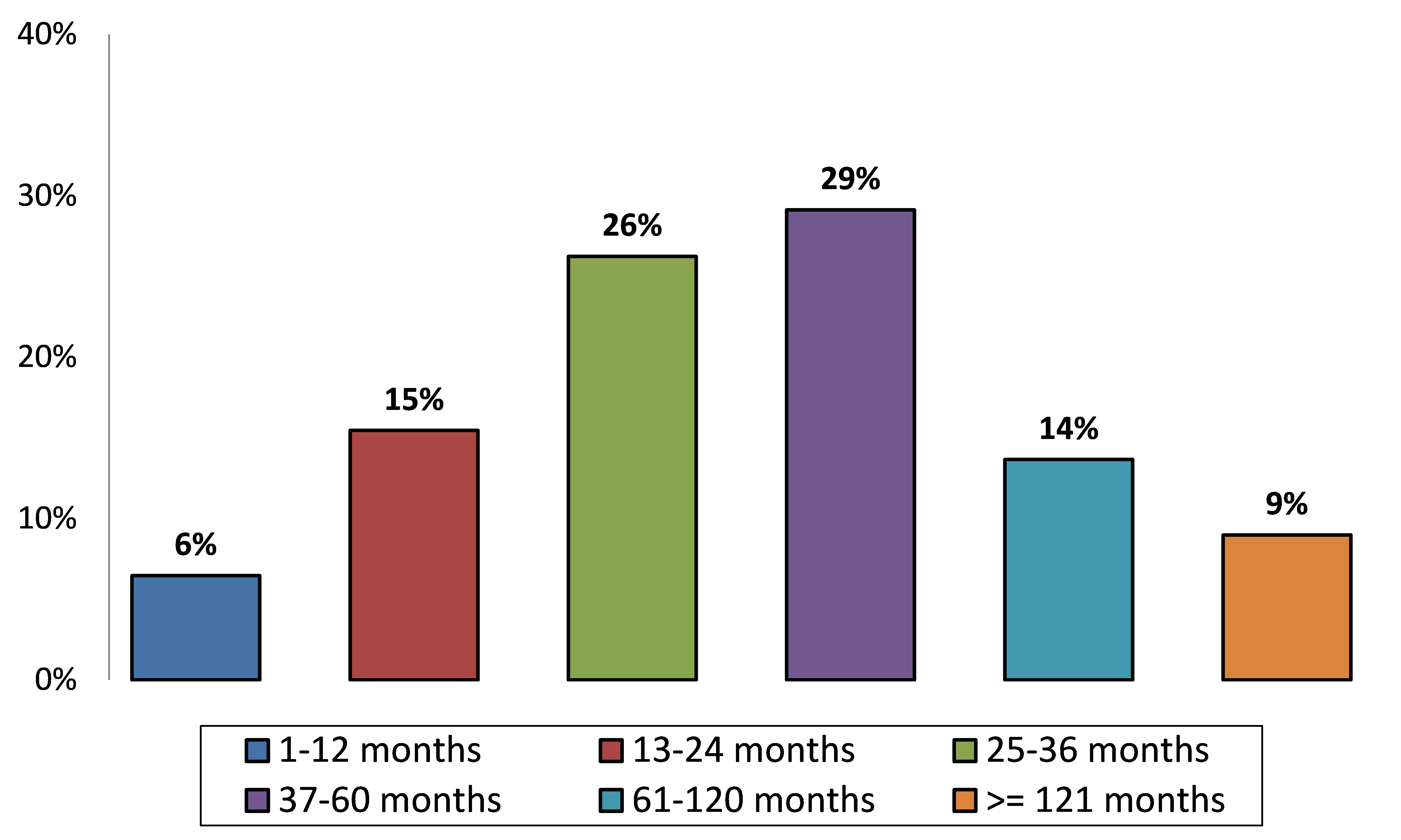

Duration of the agreements and contractual relationships

Right holders tend to have relatively long-term licensing agreements with digital content providers. Of the agreements submitted to the Commission by rights holders, four out of five have duration of at least two years and almost one out of ten have duration of over 10 years. As a result, digital content providers seeking to enter a certain market or expand their existing commercial activities in a market may face difficulties in accessing rights that are under long-term exclusive agreements between their competitors and right holders.

This issue may be exacerbated by certain contractual clauses that are part of licensing agreements – for example, first negotiation clauses, which provide for the contractual right to first renewal of the licensing agreement, automatic renewal clauses or other similar clauses. Explicit or implicit (re)negotiation clauses may affect the possibilities of new entrants and smaller operators wishing to grow their online digital content businesses.

Picture 4:

Duration of licensing agreements – proportion of all agreements submitted by right holders

7. What impact will the findings of the sector inquiry have on the future policy/enforcement of the Commission in e-commerce markets and will there be any follow-up in terms of enforcement?

The publication of the final report is the last formal step of the sector inquiry.

The insight gained from the sector inquiry will enable the Commission to target EU antitrust enforcement in European e-commerce markets, which will include opening further antitrust investigations. It will particularly target the most widespread, problematic business practices that have emerged or evolved as a result of the growth of e-commerce and that may negatively impact competition and cross-border trade and hence the functioning of the EU’s Digital Single Market.

In February 2017, the Commission already opened three separate investigations into holiday accommodation, PC video games distribution and consumer electronics pricing practices that may limit competition.

The Commission will also use the findings in order to broaden the dialogue with national competition authorities within the European Competition Network on e-commerce-related enforcement to contribute to a consistent application of EU competition rules across the EU.

Finally, the results of the e-commerce sector inquiry do not appear to question the principles of the Commission’s approach to selective distribution as reflected in the current rules for vertical agreements between companies operating at a different level of the distribution chain.